Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

The tibia is the most commonly fractured long bone. In broad terms, fractures may be divided into those affecting the proximal tibial articular surface (tibial plateau fractures), extra-articular fractures of the shaft, and those affecting the distal articular surface (pilon fractures). Of note, the latter are distinct to ankle fractures, which do not involve the weight-bearing portion of the distal tibia (the plafond). These injuries may coexist: it is relatively common to have a shaft fracture with intra-articular extension, or even separate fractures of the proximal/distal tibia and the shaft.

These fractures often result from high energy mechanisms, such as road traffic accidents (although they may also occur following low energy trauma, especially in those with osteoporotic bone). As such, it is vital to consider neurovascular injury, soft tissue compromise and compartment syndrome in all tibial fractures.

The general principles of initial assessment and management are similar for all tibial fractures, so these will be dealt with together, with differences between the injuries highlighted where appropriate.

Plateau

Shaft

Pilon

Initial assessment

These are commonly high-energy injuries – have a low threshold for an ATLS assessment and trauma call.

Always perform an initial assessment for compartment syndrome, an open fracture and neurovascular status.

History

Document time and mechanism of injury in as much detail as you can – whether the fracture has occurred with a jumping injury, a twisting mechanism, or direct trauma (dashboard injury/contact sports) has implications on the likely associated soft tissue injuries.

Ask about pain elsewhere (distracting injury).

Ask about any sensory changes in the leg.

Past medical history – specifically ask about diabetes and peripheral vascular disease.

Social history – it’s important to know the pre-injury functional status and occupation of the patient, as well as smoking status.

Examination

Inspect the skin circumferentially in order not to miss an open fracture. In addition, take careful note of any contused/bruised skin, particularly over bony prominences – an initially closed injury may become open if there is significant tension on the soft tissues.

If there is gross malalignment at any joint or fracture, proceed urgently to a neurovascular examination and consider emergent reduction of the dislocation/deformity – a fracture/dislocation of the knee or ankle must be reduced ASAP to reduce the risk of limb ischaemia.

Examine any apparently uninjured joints carefully to guide the need for further imaging – it is easy to miss an associated undisplaced ankle fracture, for example, if there is a painful displaced tibial shaft fracture.

Plateau fractures: palpation of obviously fractured areas does not change your management, but if there is an apparently isolated lateral or plateau fracture, then is is worth palpating the other side for bony tenderness which may indicate an undisplaced fracture on that side.

Shaft fractures: gently examine the knee and ankle.

Pilons: gently examine the knee, especially the proximal fibula.

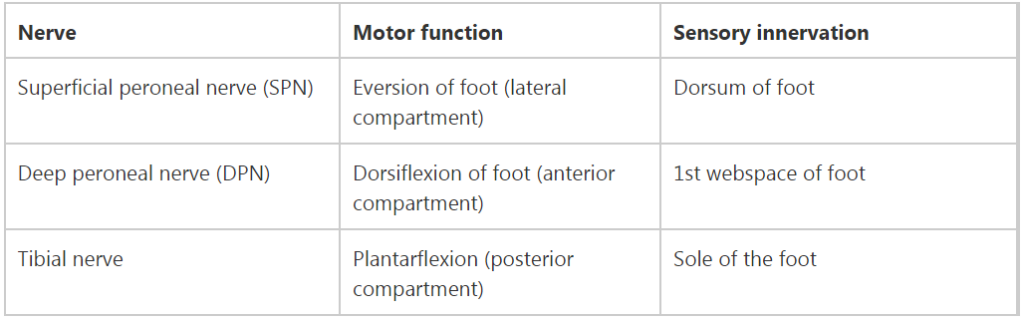

Perform a detailed neurovascular examination

- Feel the temperature of the foot compared to the other side, check capillary refill in the toes and palpate the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses. If there appears to be any deficit, call your registrar immediately!

- Tibial nerve: sensation to sole of foot, plantar flexion of toes/ankle

- Deep peroneal nerve: sensation to 1st dorsal webspace, dorsiflexion of toes/ankle

- Superficial peroneal nerve: sensation to dorsum of foot, eversion of ankle (not possible for pilon fractures)

Consider compartment syndrome if there is pain out of proportion to the injury or on passive movement of the toes.

Conduct a full secondary survey to identify any other injuries.

Imaging and classification

Obtain AP and lateral radiographs of the area of interest – if you suspect a tibial plateau fracture, get knee XRs; for the shaft, get tibia & fibular XRs, and for pilons obtain ankle views (plus proximal imaging if there is any fibular tenderness). XRs of the whole tibia are not adequate for diagnosis and management of proximal and distal fractures. If whole tibia views have been obtained, it may be appropriate to perform initial management based on these, but make sure to obtain formal views of the area of interest once the patient is immobilised.

Plateau fractures

The fracture is usually most visible on the AP. Look for splits in the articular surface and for depression of the joint line. The lateral joint line is usually a few millimetres higher than the medial, so if it is the same level or lower than the medial side, this may suggest a displaced fracture.

The lateral is often less helpful, but it may show a lipohaemarthrosis (an effusion containing blood and fat) in the suprapatellar pouch. The two components separate out, with the fat (black) floating on the blood (white), separated by a horizontal line. This may be the only sign of an undisplaced fracture:

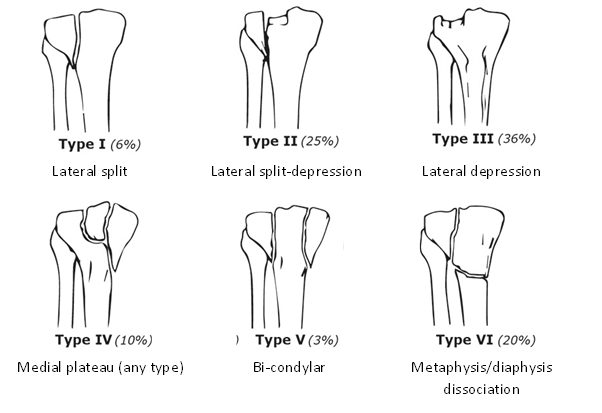

The most commonly utilised classification is that of Schatzker:

Shaft fractures

AP and lateral imaging should be obtained:

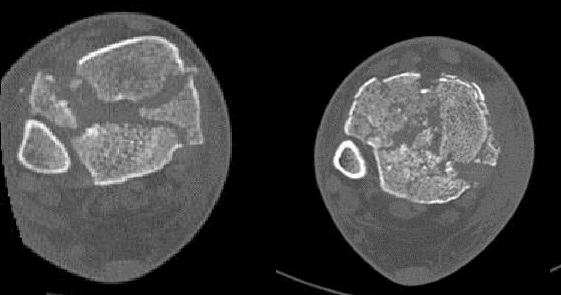

Proximal/distal fractures, especially spiral fractures, are more likely to extend into the joint, and a CT should be considered:

There is no commonly used classification for these fractures, but you should be able to describe them succinctly and accurately based on their location (proximal/mid/distal third, with or without intra-articular extension), pattern (transverse/oblique/spiral, presence or absence of comminution) and displacement (angulation, translation, rotation).

Pilon fractures

Ankle imaging is usually satisfactory, but obtain imaging of the shaft/knee if you suspect more proximal injury as well. CT is almost always required for operative planning.

There is no commonly used classification of pilon fractures, but a simple classification is that of Ruedi & Allgower:

- Type I: undisplaced

- Type II: displaced but not comminuted

- Type III: displaced and comminuted

Initial management

Ensure the patient has been adequately resuscitated and any life-threatening conditions are being managed. Manage open fractures or compartment syndrome appropriately. Open fractures may require transfer to your local major trauma unit.

If you suspect limb ischaemia, then contact your registrar urgently: the patient needs urgent reduction of the deformity, and may require surgery immediately if that does not restore perfusion.

Plateau fractures

If there is significant malalignment or joint dislocation, these require reduction with appropriate sedation, followed by application of a backslab. Do not attempt this unless you are trained in doing so. Most plateau fractures do not require reduction in the emergency department.

Apply a cricket pad splint or above-knee backslab. Keep non-weight-bearing and prescribe VTE prophylaxis.

Arrange a CT.

Keep nil-by-mouth.

Shaft fractures

The fracture should be aligned as well as possible to reduce pressure on the soft tissues. It should then be immobilised in an above-knee backslab.

Keep non-weight-bearing and prescribe VTE prophylaxis.

Elevate and monitor for signs of compartment syndrome.

Keep nil-by-mouth.

Pilon fractures

As for ankle fractures, these should be reduced in the emergency department. Do not attempt this if you have not been trained in doing so – make sure it happens in the ED however and call your senior if necessary.

Keep non-weight-bearing and prescribe VTE prophylaxis.

Elevate and monitor for signs of compartment syndrome.

Keep nil-by-mouth.

Checklist

- ATLS primary and secondary surveys performed

- Initial history and examination (including NV exam) documented

- Open fracture/compartment syndrome management initiated if indicated

- Fracture reduced if required

- Appropriately immobilised

- Post-reduction/immobilisation imaging and NV examination documented

- VTE prophylaxis prescribed

- Elevated

- Analgesia, laxatives and anti-emetics prescribed

- CT requested if required

- Made nil-by-mouth

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

When to call a senior urgently

- Open fracture (unless you are happy to manage appropriately in ED and arrange transfer to your local major trauma unit)

- Suspected compartment syndrome

- Neurovascular deficit that persists after reduction or is new following reduction

- Knee dislocation

- Unable to reduce in ED, or ED are unwilling/unable to reduce

Admission and discharge

- You will never be wrong to admit a tibial fracture

- Patients with undisplaced fractures following low energy trauma, who can safely non-weight-bear at home, may be suitable for discharge and early fracture clinic review, but if you are not certain about this, always discuss with a senior

Definitive management

Plateau fractures

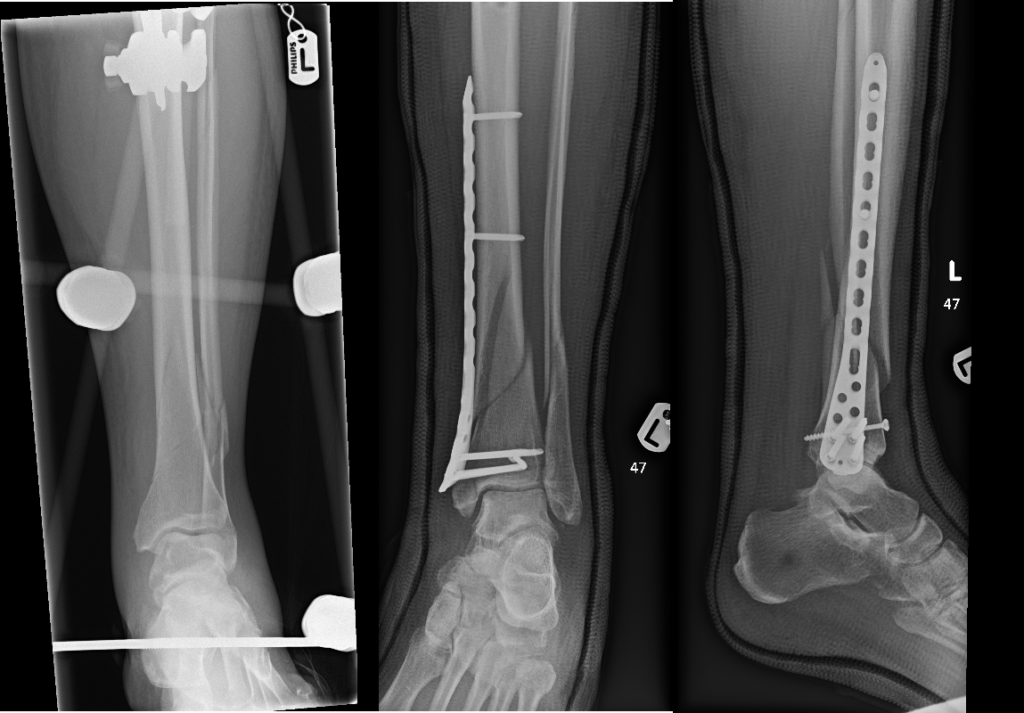

Displaced tibial plateau fractures are usually managed with open reduction and internal fixation:

If a fracture is significantly displaced and there is likely to be a delay to surgery, a spanning external fixator may be applied. Occasionally an external fixator may be used as definitive treatment.

Shaft fractures

These may be managed in a number of ways. It is not possible to fully explain the decision making process here, nor is that necessary knowledge for most SHOs.

Non-operative management involves a significant period of cast immobilisation and non-weight-bearing and is typically reserved for minimally displaced, stable fracture patterns.

Open reduction and internal fixation with plates may be indicated, particularly for very distal or proximal fractures, but requires significant soft tissue stripping with the attendant risks of infection and non-union. It may also be indicated if the diaphyseal canal is very narrow and nailing is not possible.

Definitive management with an external fixator is an option. It allows early weight bearing, requires no soft tissue stripping, and results in no retained metalwork, but carries risks of pin-site infection and is a significant burden for the patient.

If technically possible, intramedullary nailing is widely used. It does not usually require any opening of the fracture site, and normally permits early full weight bearing.

Pilon fractures

The management of pilon fractures is complex and somewhat controversial. They should be managed by a consultant with subspeciality interest in lower limb trauma, and may require plastic surgical input even if closed.

Particularly if early surgery is not possible (due to surgeon availability or soft tissue swelling) they may require temporary external fixation. Definitive management may be non-operative (especially if undisplaced), with external fixation or with internal fixation.

Guidelines

There are no specific guidelines for managing these injuries.

NICE NG37 (complex fracture assessment and management) briefly mentions the logistics of pilon fracture management:

- Create a definitive management plan and perform initial surgery (temporary or definitive) within 24 hours of injury in adults (skeletally mature) with displaced pilon fractures

- If a definitive management plan and initial surgery cannot be performed at the receiving hospital within 24 hours of injury, transfer adults (skeletally mature)

- with displaced pilon fractures to an orthoplastic centre (ideally this would be

- emergency department to emergency department transfer to avoid delay).

- 1.2.34 Immediately transfer adults (skeletally mature) with displaced pilon fractures to

- an orthoplastic centre if there are wound complications.

NG37 also refers to how to assess patients with tibial fractures for compartment syndrome, including:

- Regularly assessing and recording clinical symptoms and signs in hospital

- Considering continuous compartment pressure monitoring in hospital when clinical symptoms and signs cannot be readily identified (for example, because the person is unconscious or has a nerve block)

- Advising people how to self-monitor for symptoms of compartment syndrome, whenthey leave hospital

The BOAST guidelines for compartment syndrome and open fractures are also relevant to these injuries

Page details

Author: India Cox

Editor: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 27/04/2020