Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Definitive management and complications

Overview

Shoulder dislocations are very common. The vast majority will be dealt with by the Emergency department (ED) without your involvement. Patients you are likely to be referred include:

- Dislocations with an associated fracture (fracture dislocations)

- Dislocations that are irreducible by ED

- Posterior dislocations

- Routine dislocations when ED is busy

- Recurrent dislocations/subluxations

Initial assessment

The assessment of patients presenting with a shoulder dislocation varies hugely depending on their exact circumstances:

- If presenting as part of a high energy injury, then they need ATLS assessment, possibly as part of a trauma call

- An isolated, relatively low energy injury in an otherwise healthy young person (often football or rugby injuries) requires a more focussed assessment

- Elderly patients may present following minor trauma, or with a chronically painful and stiff shoulder due to a missed dislocation several weeks or more ago. Not infrequently the fall was due to an underlying medical problem and/or has led to a long lie. These patients require a thorough assessment for medical causes of the fall, associated injuries and sequelae of a long lie, and often require fluid/antibiotic therapy etc. The NOF page has a thorough overview of this type of assessment.

- Posterior dislocations may occur following seizure and electric shock. Take a careful history (especially to elicit the former – hopefully the latter will be more obvious) and refer to the medics/neurologists as appropriate for post-seizure care; once their shoulder is in joint they should not really need admitting under T&O.

- Some patients are able to voluntarily dislocate their own shoulders, and can usually relocate them as well. This may be associated with mental health problems and they may have personalised ED management plans. Their initial management however is similar to any traumatic dislocator; if you are planning to deviate from this, then discuss with a senior.

History

What was the mechanism of injury (high or low energy, what position was the arm/shoulder in, what force was applied to the arm, did the patient feel a clunk/pop)?

Do they have any tingling or numbness in the arm/hand?

Has the patient had any previous dislocations? If so, how were they reduced?

Have they had any previous surgery to that arm/shoulder?

Examination

Inspect the shoulder and arm. Look for loss of the usual rounded contour of the shoulder, which instead may look ‘squared off’:

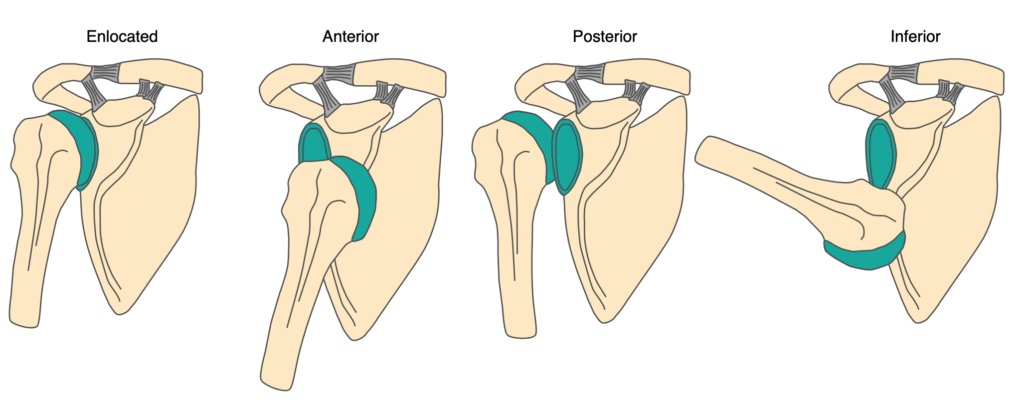

Look at the position of the shoulder/arm. Although not hard and fast rules, an anterior dislocation usually leads to adduction and external rotation, posterior dislocations are usually adducted and internally rotated, whilst inferior dislocations may be fully abducted.

Look for any open wounds (rare for pure dislocations, but more common with fracture dislocations).

Feel gently along the bony prominences of the shoulder girdle (SCJ, clavicle, ACJ, acromion, humeral head and greater tuberosity. Although a dislocation is a painful injury, gentle bony palpation without moving the joint should not hugely increase their pain. If it does, consider a minimally displaced fracture.

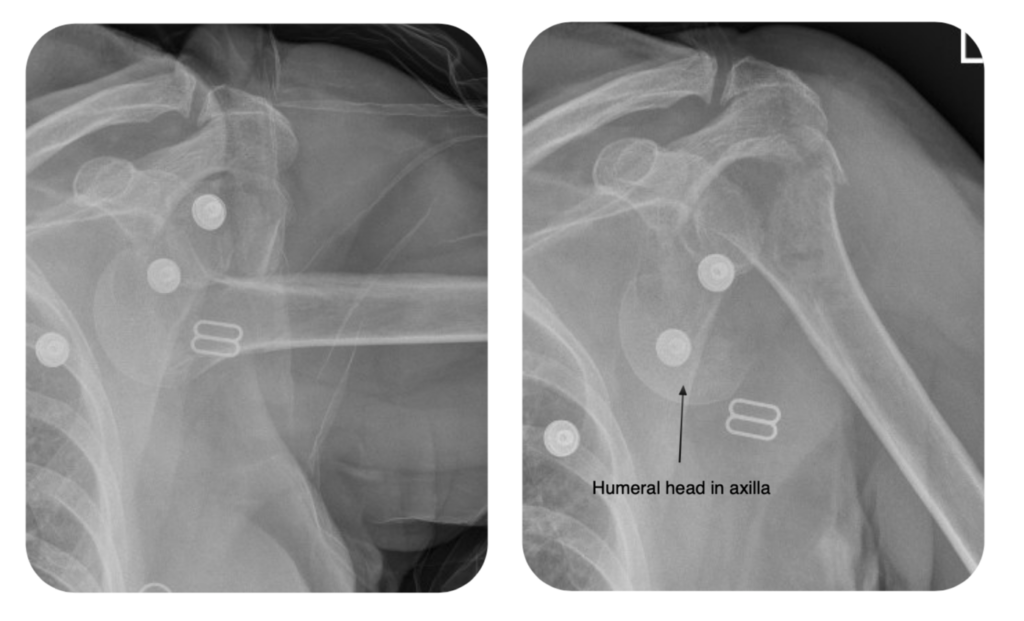

NB with an anterior or inferior dislocation, the humeral head is most commonly in the axilla.

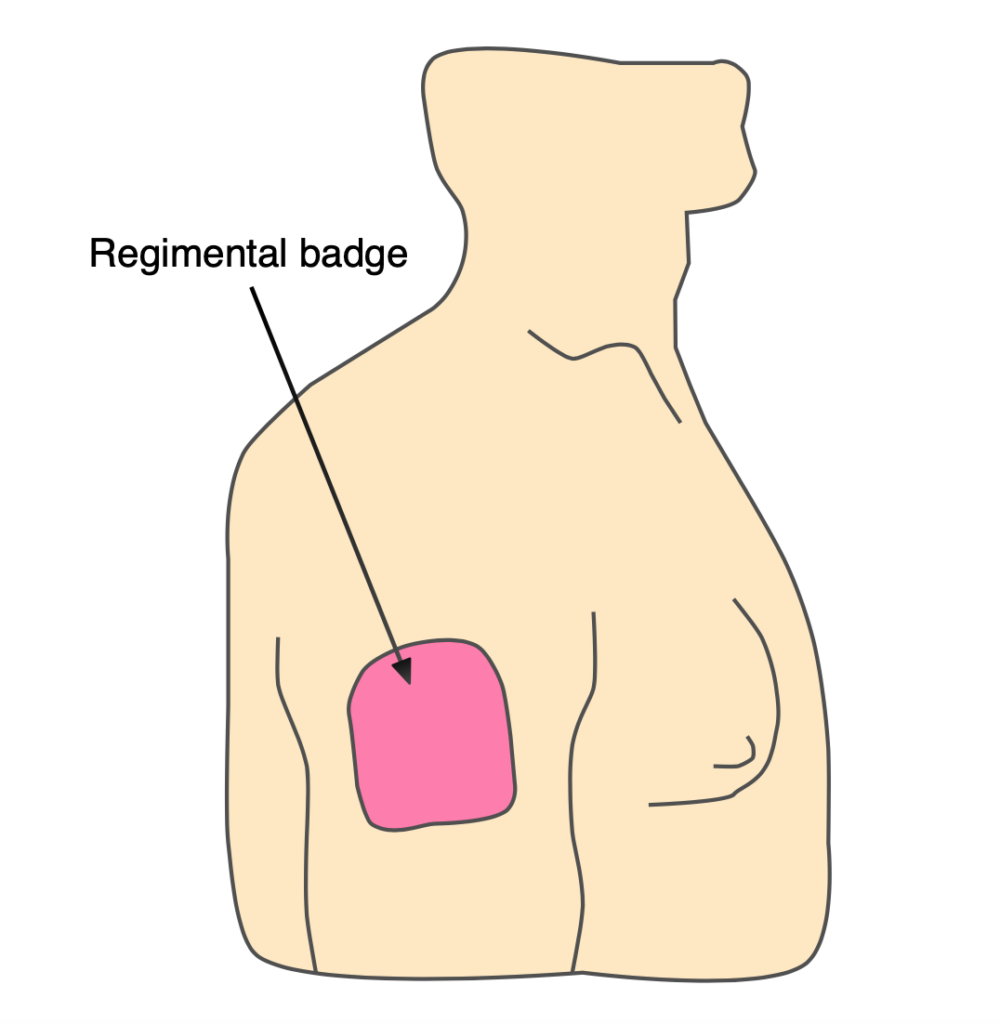

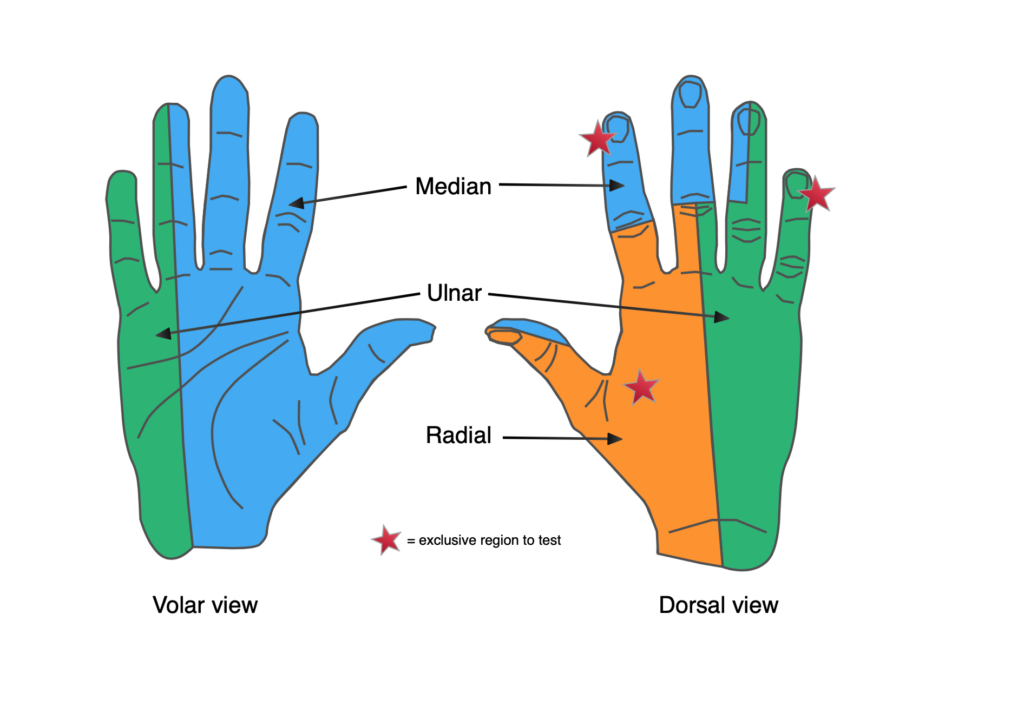

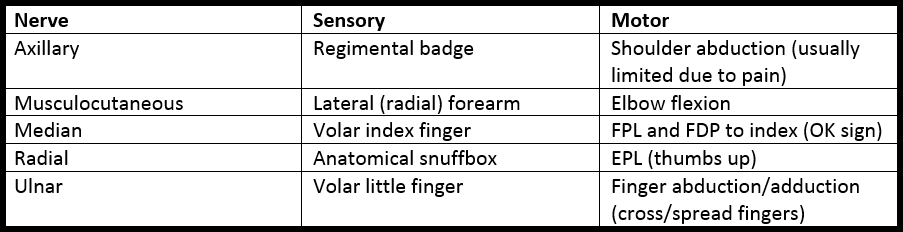

Perform a full neurovascular assessment. Whilst the joint is dislocated, patients are often unable/unwilling to try and abduct their arm, but make sure you document axillary nerve sensation. Check radial, ulnar and brachial pulses, capillary refill and distal temperature.

Imaging and classification

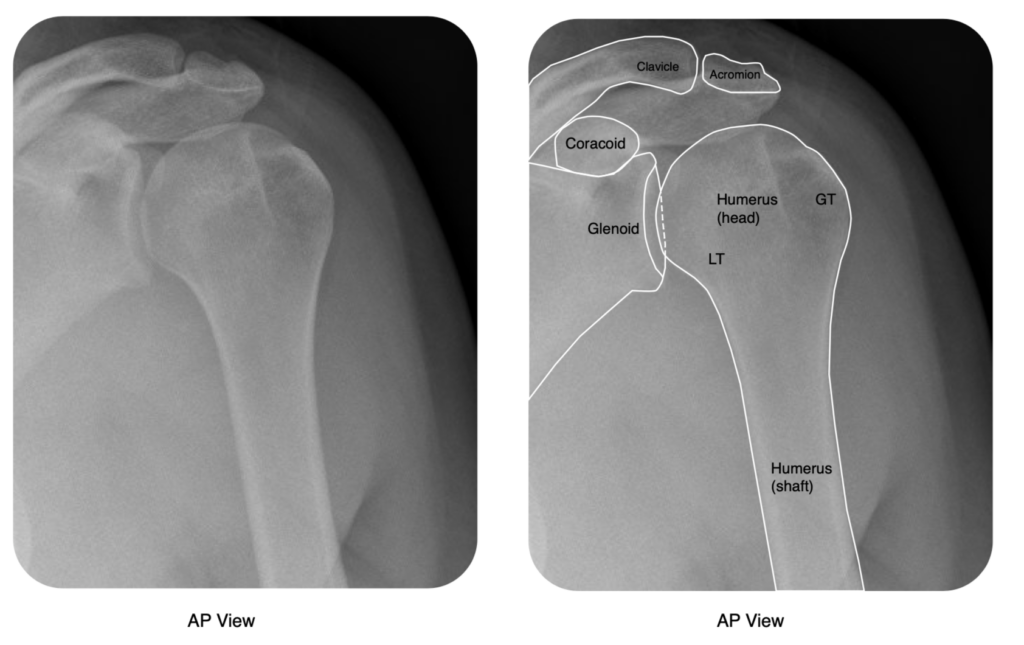

Shoulder radiographs

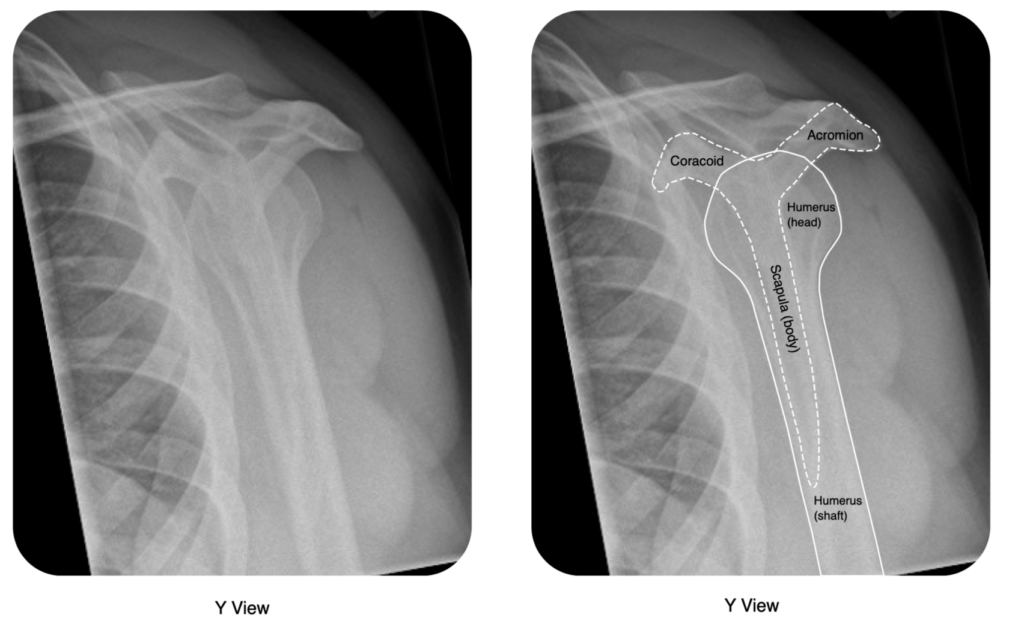

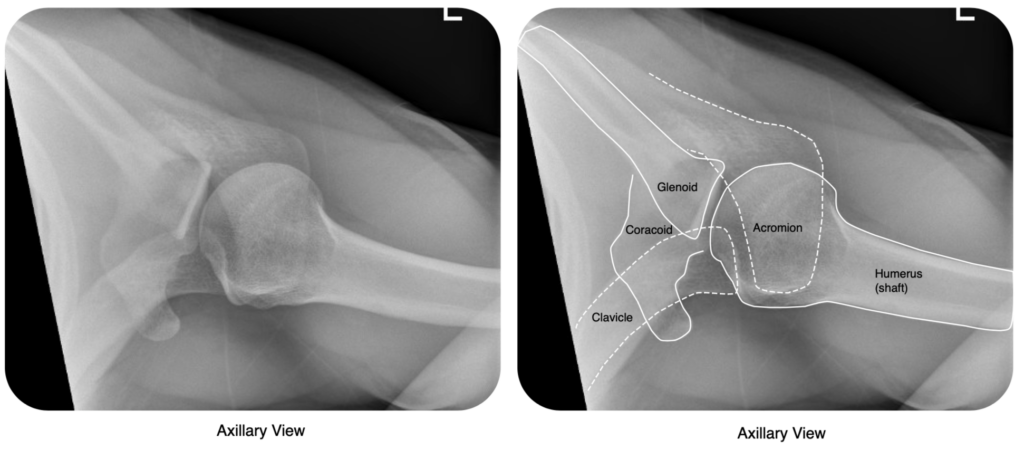

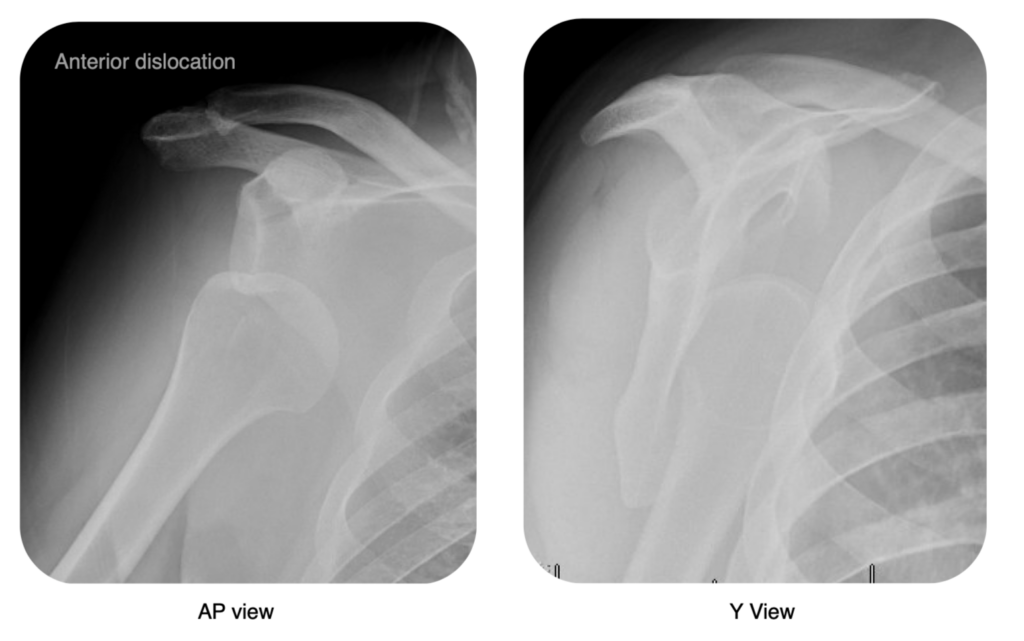

All patients require a minimum of two views. One should be an AP, whilst there should also be lateral (trans-scapular) Y-view and/or an Axillary view.

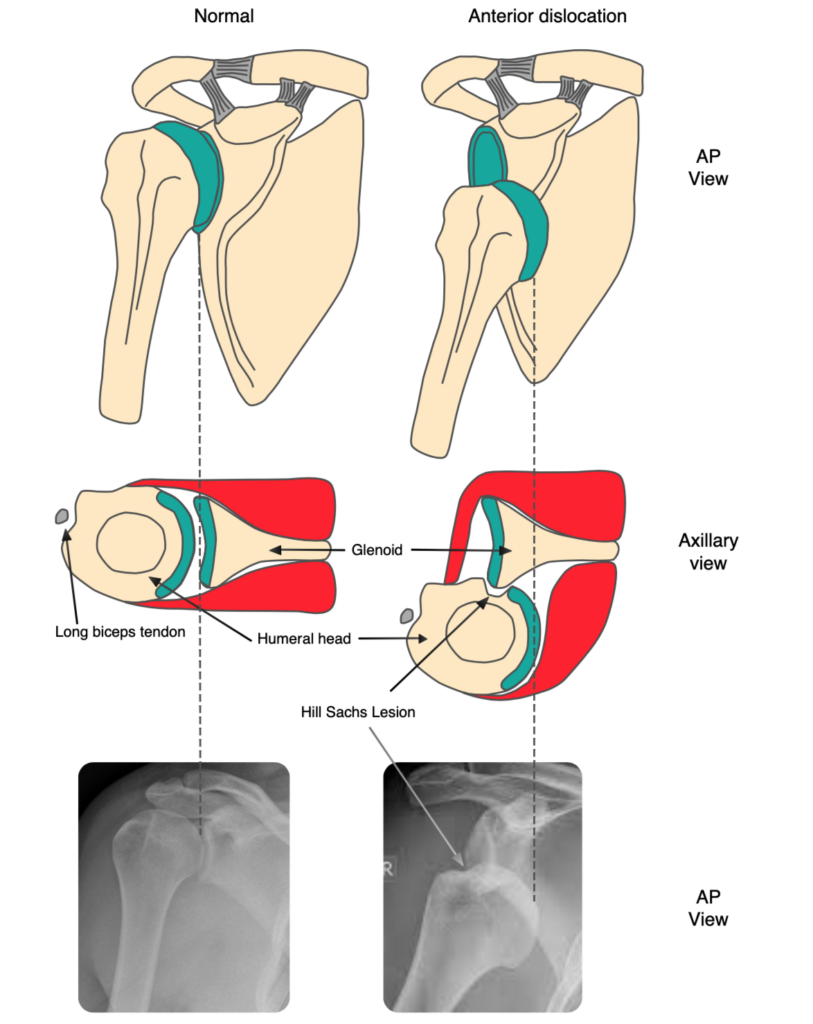

The axillary view, in particular, is excellent to clarify the direction of dislocations, visualise Bankart & Hill-Sachs lesions, and rule out a dislocation (in conjuction with the AP). It can be difficult to obtain however as it requires the shoulder to be abducted.

Top Tip. If an axillary view cannot be obtained, ask for a Velpeau view/modified axillary. You might have to demonstrate to the radiograpghers. It provides most of the information that an axillary does, but is much more comfortable for a patient with an injured shoulder:

If you still cannot rule out a dislocation, then obtain a CT scan.

Classification by direction of dislocation

There are 3 types of shoulder dislocations: anterior, posterior and inferior, which refer to the direction of displacement of the humeral head:

Anterior dislocations account for approximately 95% of all shoulder (glenohumeral) dislocations and result from an external rotation and abduction force:

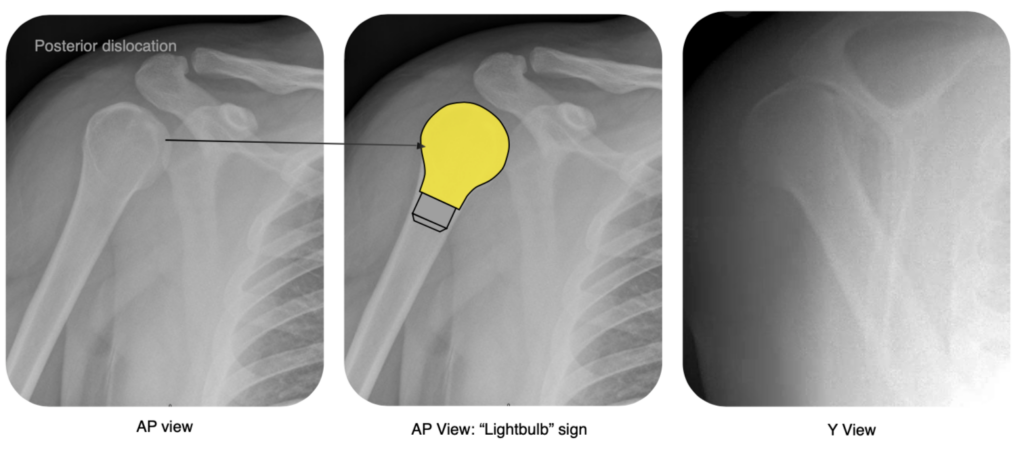

Posterior dislocations account for approximately 5% of all shoulder dislocations and result from an internal rotation and adduction force. Posterior dislocations can be quite subtle and are often missed. You need to look out for the “lightbulb” sign, which is a very symmetrical-looking humeral head on the AP (due to internal rotation):

Inferior dislocations (luxatio erecta) are very rare and result from forceful hyperabduction of the shoulder (e.g. falling from scaffolding and grabbing hold):

Other factors to consider when describing an injury

Time course: most shoulder dislocations present acutely (within hours), but some have a delayed/subacute presentation (days-weeks). If a dislocation is missed, is impossible to keep reduced, or a decision is made not to reduce, it may become chronic (weeks-months-years).

Frequency: is this the first dislocation, or one of many?

Mechanism/cause:

- Traumatic: due to an acute injury

- Atraumatic structural: dislocated without injury, but due to an abnormality of the shoulder (including due to prior injury)

- Habitual non-structural: dislocated voluntarily or due to abnormal muscular activity, with a structurally normal shoulder

Presence or absence of a fracture

Initial management

A dislocated shoulder needs to be reduced or relocated as soon as possible. Once this is done, the patient will be in significantly less pain and the majority can discharged. This initial management is often the only treatment these patients need.

Do not allow a dislocated shoulder that has not been reduced to leave ED (either to the ward or home) without discussing with your senior.

Do not attempt any reduction manoevres if you have not received appropriate training – injudicious attempts at reduction may cause an iatrogenic fracture. Even if you are not able to perform the reduction yourself, however, you can make sure everything is organised:

- Documented neurovascular examination

- X-rays – never attempt reduction without them

- Analgesia/sedation (entonox, penthrox, or IV sedation; if there has been a failed reduction with entonox, do not try again without stronger sedation) and someone to provide it

- A folded up sheet for counter-traction and someone to hold it

After the reduction has been performed, you must:

- Place the patient in a broad-arm sling (for an anterior or inferior dislocation; posterior dislocations should be kept in external rotation – you may need to improvise with pillows overnight, then get an external rotation brace)

- Re-check and document neurovascular status

- Arrange a check X-ray

Fracture dislocations

The most common fracture dislocation involves an anterior dislocation with an associated greater tuberosity fracture. This is relatively benign, and can usually still be reduced in the ED, although any methods requiring forceful rotation (e.g. Kocher’s) should be avoided. Beware the undisplaced humeral neck fracture, which is hard to see on initial radiographs, but which may end up with the humeral head left in the axilla, an absolute disaster:

Definitely discuss any fracture dislocation with an orthopaedic senior. It may be possible to reduce in ED with appropriate sedation and modified reduction manoeuvres, but they may require reduction in theatre with a GA and muscle relaxant.

Checklist (for simple anterior dislocation)

- Initial assessment including neurovascular examination

- Radiographs reviewed

- Reduction carried out

- Post-reduction radiographs reviewed

- Post-reduction neurovascular examination

- Appropriate immobilisation provided

- Fracture clinic referral made

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

When to call a senior urgently

- Fracture dislocation

- Neurovascular deficit that does not resolve after reduction

- New neurovascular deficit after reduction

- Open injuries

- Inability to reduce in ED

Most other shoulder dislocations can be discharged direct from ED with fracture clinic follow up arranged.

Definitive management and complications

Definitive management

Most shoulder dislocations do not need any operative management. The majority do not recur, and require only a sling for comfort followed by physiotherapy. Surgery may be required if there is an associated rotator cuff injury, or if they are recurrent, often due to the complications below.

Hill-Sachs lesion

This is a postero-lateral humeral head compression fracture. It results from impaction of the humeral head against the antero-inferior glenoid rim. A large Hill-Sachs lesion may cause recurrent instability. A reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (antero-medial compression fracture) is seen in a posterior dislocation.

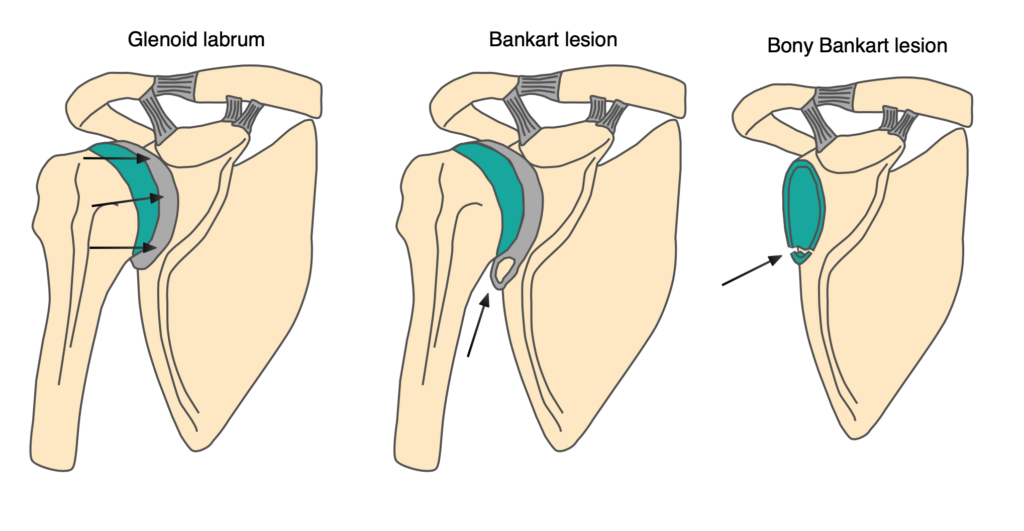

Bankart lesion

This is an avulsion of the antero-inferior labrum of the glenoid and is associated with Hill-Sachs lesions. The labrum and capsule are vital for stability of the shoulder and any injury to these structures will predispose the patient to recurrent dislocations. A true Bankart lesion is a soft tissue injury and you can assume most patients who have suffered an anterior dislocation have one. You may also see a fracture of the antero-inferior glenoid rim and this is termed a “Bony Bankart” lesion.

Page information

Author: Andrew Gardner

Editor: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 21/04/2020