Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

Total hip replacements (THRs) are a very successful operation, but one of the major risks is dislocation. Patients typically present with pain in/around the hip, deformity and inability to weight bear. Not infrequently, patients dislocate recurrently and may be able to tell you what has happened.

THRs dislocate much more frequently than hemiarthroplasties; the larger head and limited soft tissue excision for a hemiarthroplasty reduce the dislocation risk significantly. Despite this, hemiarthroplasties do dislocate. The same principles as apply to THR dislocation can be utilised for dislocated hemiarthroplasties.

Initial assessment

If the dislocation has resulted due to trauma, consider an ATLS assessment

History

What led to the dislocation? There may be a history of trauma (e.g. falls), but more commonly the dislocation occurs due to abnormal positioning of the leg. It is important to document the position of the leg at the time of dislocation.

Generally, posterior dislocations occur due to hip flexion (e.g. sitting on a low chair or bending over), whilst anterior dislocations occur in hip extension with internal rotation (e.g. crossing legs or rolling over in bed).

How many dislocations has the patient had, when did any previous dislocations occur, and what led to those?

When was the hip implanted, and has the patient had any subsequent surgeries on the hip?

Are there any symptoms suggestive of infection (pain, fevers, rigors)?

Make sure to take a full past medical, drug and social history – the patient may require major revision surgery.

Examination

Check neurovascular status

- Pedal pulses

- Capillary refill

- Femoral nerve function (anterior thigh sensation, ability to contract quadriceps)

- Sciatic nerve function (dorsum of food sensation, ability to dorsiflex ankle)

Check leg lengths – posterior dislocations normally lead to a shortened leg; anterior dislocations may lead to leg lengthening

Check hip rotation – an anterior dislocation usually leads to external rotation, whilst a posterior dislocation usually leads to internal rotation

Initial management

Arrange relocation under sedation in ED.

If relocation in ED is not possible (e.g. not safe to sedate, no staff available to sedate, or attempted reduction fails), prepare the patient for a general anaesthetic:

- Bloods, ECG, CXR as indicated

- Keep nil by mouth

- Consent for manipulation under anaesthetic (MUA) if you feel capable

Following reduction:

- Re-check neurovascular status

- Arrange check XR (AP/lateral)

- Mobilise with physiotherapists

- Decide whether admission is required

Imaging and classification

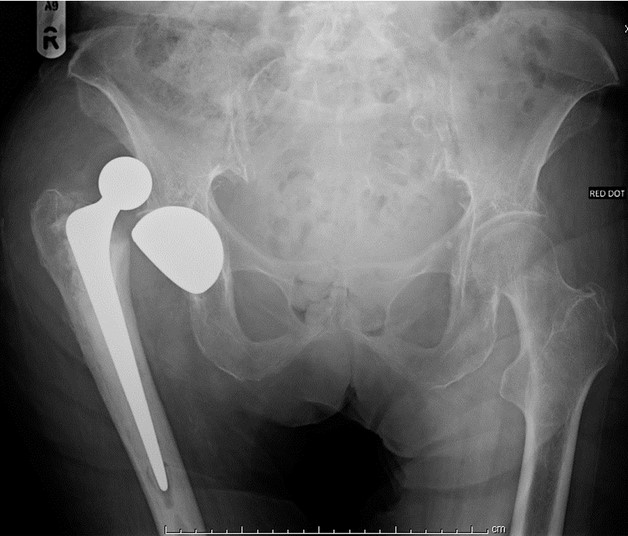

The diagnosis is usually clear from the AP pelvis radiograph:

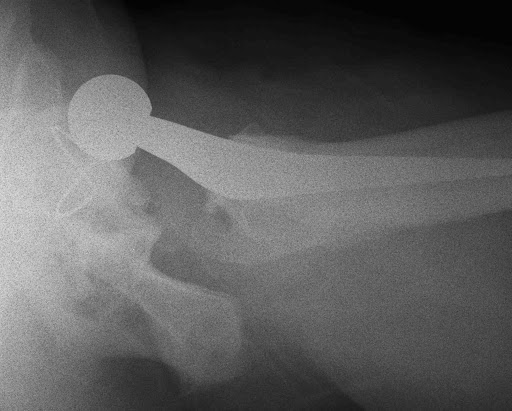

If the AP looks normal, but you remain suspicious of a dislocation, then a lateral will help. The lateral may also help decide whether the dislocation is anterior or posterior (although the location of the femoral head can change following the initial dislocation):

Classification & description

There is no frequently used classification for THR dislocations, but the following criteria can be used to accurately describe the injury:

- The hip: revision or primary (or hemiarthroplasty)

- Mechanism: traumatic or atraumatic

- Direction: anterior, posterior or unclear

- Frequency: first or recurrent

- Time since index surgery

- Any complications (e.g. periprosthetic fracture or implant loosening)

Post-reduction XRs

The most important feature is whether or not the hip has been relocated (although this ought to be apparent clinically) and whether the joint is congruent. Occasionally a piece of entrapped soft tissue can prevent full relocation, making the hip highly likely to re-dislocate. If you see this, keep the patient NWB and discuss with a senior:

If excessive force is used during reduction manoevres, the stem can pull out of its cement mantle. Again, if this occurs, keep the patient NWB and discuss with a senior:

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

When to call a senior:

- Irreducible THR with neurovascular deficit

- ED unwilling to attempt reduction

- New neurovascular deficit following reduction

Patients to admit

Some centres admit all dislocated THRs for physiotherapy review, but in most hospitals, once the THR has been reduced, patients can be discharged from the ED if they pass a physio review. The following patients should always be admitted however:

- Unable to reduce in ED (keep NBM for reduction in theatre on next available list)

- Periprosthetic fracture, stem subsidence or stem pullout

- Patients not safe for discharge despite THR reduction

- Concerns of infection

Patients to discharge

Patients not meeting any of the above criteria may be discharged from ED, but it is sensible to take their details and ensure they are followed up, ideally by their original operating surgeon.

Checklist

- Documented history and examination

- AP and lateral X-rays

- Reduction under sedation in ED if appropriate

- Post-reduction neurovascular examination and XRs

- If reduction not possible: keep NBM for next available list and consent for reduction in theatre

- Decision RE admission/discharge

- Details kept to arrange follow up if discharging

Definitive management

Reduction

The reduction techniques used vary depending on the direction of dislocation. The principles are to use as little force as possible and to avoid twisting movements with any force. If you have not been trained in their use, do not attempt the reduction yourself, but the techniques are outlined below for interest.

Before attempting any reduction, make sure the patient is as sedated as possible. You might succeed with entonox or penthrox, but IV sedation works best. If you’re performing the reduction in theatre and are struggling, ask for muscle relaxant.

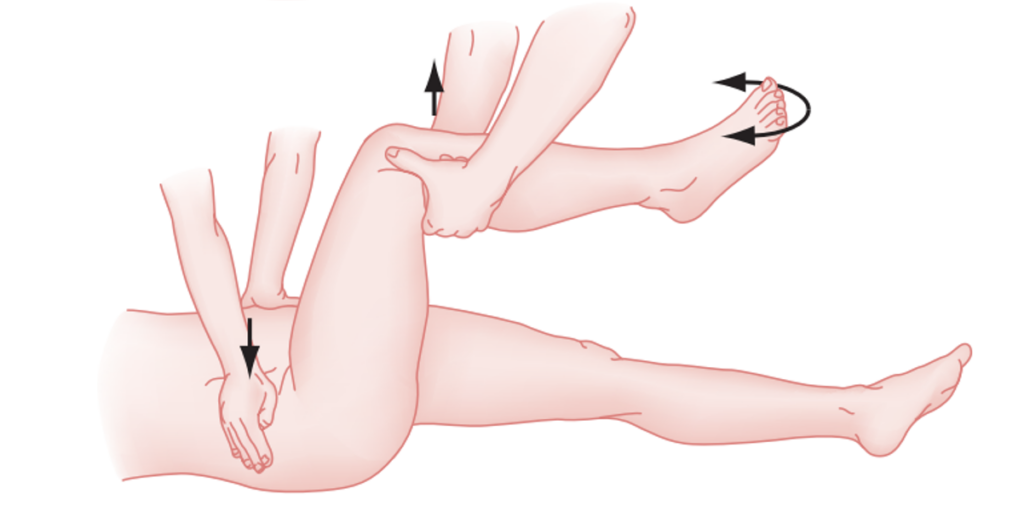

For posterior dislocations, the “90/90” position works best. The patient’s hip and knee are flexed to 90 degrees, and the reducer pulls along the long axis of the femur. An assistant should push down on both ASISs to prevent the patient from lifting off the table. Before I start pulling, I gently increase the internal rotation of the hip, to try and disimpact the femoral head from the posterior wall of the acetabulum, reducing the risk of pulling out the stem or loosening the cup.

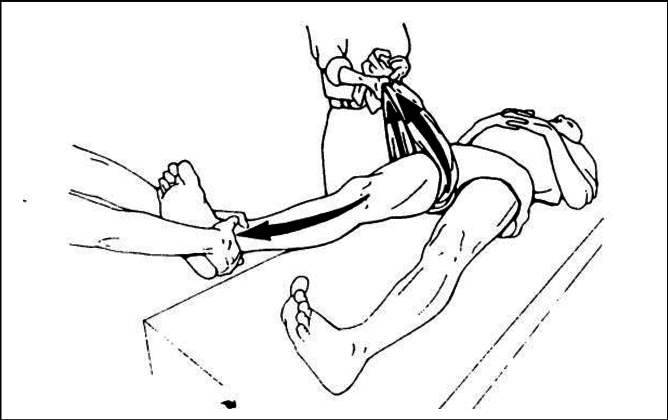

For anterior dislocations, simple in-line traction on the leg, with slight increased external rotation normally works. An assistant should push up (towards the head) on the ASISs to stop the patient sliding down the table. If a second assistant is available, and simple traction hasn’t helped, then they can pull the femur out laterally to try and disimpact the femoral head further:

Post-reduction conservative measures

To reduce the risk of further dislocations, patients should be re-educated on “hip precautions”. Patients who have suffered a posterior dislocation should particularly avoid hip flexion (e.g. sitting on low chairs), whilst those with an anterior dislocation should particularly avoid external rotation (e.g. crossing legs). The physiotherapists are best placed to provide this eduction.

Physiotherapy to increase muscle strength and proprioception (especially abductors and short external rotators) may be of benefit, as may hydrotherapy.

Braces may be of benefit. In the short term a Charnley wedge between the legs may help with either direction of dislocation. A cricket pad splint (prevents hip and knee flexion) may be of use with a posterior dislocation, whilst the toes can be tied together (prevents external rotation) to prevent an anterior dislocation. In the longer term, orthoses such as an abduction brace may be worn whilst mobilising.

Revision surgery

Hip revision surgery is a major undertaking, and for that reason it is unusual to perform revision for a single dislocation episode (unless there is a fracture, hardware loosening or stem pullout, or the dislocation happens soon after the index surgery and there is gross component malpositioning). If a patient recurrently dislocates, then revision surgery may be indicated. The surgery itself may take many forms and depends on the reason for the dislocation(s).

Patient factors (e.g. muscle weakness, frequent falls) should be corrected as far as possible, and non-operative measures exhausted, before revision surgery is considered.

The cup and stem must be appropriately sized and oriented. If they are incorrectly sized or positioned, then correcting this may be all that is required. If no identifiable cause is identified, then a change in articulation (e.g. a larger head, dual mobility or constrained acetabular component) may be indicated. In unsalvageable situations, implant removal or leaving the components dislocated may be considered.

Decision making in dislocated THR is beyond the scope of this website, but Orthobullets is an excellent higher level resource.

Page details

Author: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 29/03/2020