Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

Periprosthetic femoral fractures are any femoral fracture in a patient who has had a hip replacement. They may occur intra-operatively (caused by the operation itself) or post-operatively (typically following a fall). You are most likely to encounter the latter situation, but occasionally an intra-operative fracture is not recognised at the time of operation, and it is worth considering if a post-operative patient has greater than expected levels of pain.

Most of the principles of assessing and managing a periprosthetic femoral fracture are similar to those regarding hip fractures. Here we will primarily aim to highlight any differences between the two sitations.

As with all trauma, if you are concerned regarding a high-energy mechanism of injury, or multiple injuries, assess the patient according to ATLS and have a low threshold to ask for senior help.

Initial assessment

Consider a trauma call and ATLS assessment if appropriate.

Most aspects are similar to the initial assessment of a hip fracture. Any additions or differences are highlighted below.

History

It is important to get as much information about the hip replacement itself as possible. This may be from the patient, hospital records, or a combination of the two. Specifically, try and find out:

- When was the hip replacement performed?

- Who did it and where?

- Have there been any complications (e.g. wound infections or dislocations) or re-operations (e.g. wound washouts, DAIR procedures, or revisions), and if so when, where and by whom?

- Prior to the recent injury, was the hip replacement painful? Ask specifically about pain in the groin, anterior thigh, lateral thigh and knee

Examination

As per a hip fracture, plus documentation of the state and location of their previous scar(s).

Investigations

Obtain initial imaging and pre-operative investigations as per the hip fractures page. Ensure that you get AP and lateral plain radiographs of the whole femur for operative planning. In most cases a CT is also of great value; this is not strictly required urgently, but the sooner the better to minimise delays, so if you can obtain one in the ED, then do so.

Initial management

Again, the simplest approach is to manage these patients like a hip fracture. If your trust has a hip fracture proforma or booklet, then use that to ensure you don’t miss anything. This also applies to your discussions with other specialities (e.g. ED); periprosthetic fractures are not as common or as well-understood as hip fractures, but if you just say “manage them like a NOF” then most people will know what to do.

The only real exception to management is regarding the use of traction, which is more commonly useful in these injuries, especially if there will be a delay to surgery. There are no hard-and-fast rules, but I would consider applying skin traction to any significantly displaced Vancouver B fracture, and any Vancouver C fracture (see below).

In addition to managing the patient, you must start to think about the logistics of planning a complex operation. Periprosthetic surgery is generally longer, more complex and higher risk than hip fracture surgery. Consider the following:

- Urgently requesting patient records, especially old operation notes (contact the appropriate hospital if the operation was done elsewhere)

- Arranging an anaesthetic review

Imaging and classification

As mentioned above, obtain AP and lateral XRs of the whole femur. Comparison with old images of the hip replacement (if available) can be very helpful. A CT is almost always helpful for pre-operative planning.

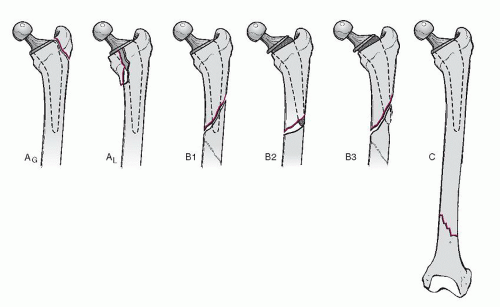

The most commonly utilised classification for periprosthetic femoral fractures is the Vancouver classification. It is useful to know that this was developed only for use with uncemented femoral stems; in the UK, most hip replacements are with cemented stems, which makes the classification less useful for predicting required surgical treatment, but it remains widely used for all types of periprosthetic femoral fracture.

The Vancouver classification is based on the level of the fracture (relative to the implant), whether the implant is well fixed or loose, and the pre-fracture bone stock. Detailed knowledge of the latter two is well beyond SHO level.

Vancouver type A fractures are metaphyseal fractures of either the greater or lesser trochanter, with a well-fixed stem. They may be termed A(G) and A(L) respectively.

Vancouver type B fractures are diaphysial fractures either around the stem/cement or immediately distal to its tip. They are subdivided further. A B1 fracture is associated with a well-fixed stem. A B2 fracture is associated with a loose stem (either before, or as a result of, the fracture), but with good bone stock. A B3 fracture has grossly deficient bone stock, either due to the fracture or (more commonly) from pre-existing osteolysis.

Vancouver type C fractures are well distal to the stem/cement. They are not really periprosthetic fractures at all, apart from that the femoral stem affects management options.

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Who to admit: all periprosthetic fractures

When to call a senior urgently:

- Most periprosthetic fractures do not need urgent senior review – this can wait until the morning unless you have specific concerns (e.g. associated arterial injury)

- If you require help with medical optimisation, call the appropriate medical specialist

Checklist

- NOF proforma completed

- Full clerking history (Hx, PMHx, DHx, SHx) recorded, including pain/symptoms from hip replacement prior to injury, and operative details

- Secondary survey recorded

- ECG, CXR and bloods recorded

- Hb >100 or transfusion arranged

- Cannula sited and IV fluids prescribed

- Regular medications written up

- Contra-indicated medicines being held

- Anticoagulation being reversed

- Analgesia (including nerve block), anti-emetics and laxatives prescribed

- Traction considered

- Nutritional support prescribed

- Pressure area care being managed

- Resuscitation decision documented

- Next of kin aware (if appropriate)

- Old notes and operation notes requested

- CT requested

Definitive management

The definitive management of periprosthetic femoral fractures is well beyond SHO level, and decisions regarding these fractures should be made by consultant surgeons with a subspeciality interest in lower limb trauma and hip arthroplasty. The information below is a guide to the concepts involved.

Treatment options

Non-operative treatment may involve a period of non-, touch- or partial-weightbearing. It is the least common treatment for periprosthetic femoral fractures.

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) typically involves the use of cerclage cables (wire cables that are passed around the femur and then tensioned to hold fracture fragments together), with or without metal plates. It may be used alone, or with femoral stem revision.

Revision hip replacement involves removing the old implant and inserting a new, typically longer, one. When performed for a periprosthetic femoral fracture, it will always involve a femoral stem revision; the acetabular component (if present) may also be revised (e.g. if it is also loose, or to provide greater protection against dislocation of the revised femoral stem). Revision is usually more of a physiological challenge (longer operation with higher blood loss etc.) than ORIF.

Treatment choice

Vancouver A fractures may be managed operatively or non-operatively. Minimally displaced A(G) fractures would typically be managed with a period of restricted weight-bearing, whilst displaced fractures might benefit from operative fixation to restore abductor function and reduce the risk of a Trendelenberg gait. A(L) fractures may be managed with a period of restricted weight bearing, but they increase the risk of future stem loosening, so may undergo ORIF with cerclage cables.

Vancouver B1 fractures are typically managed with ORIF with cables and a plate. Vancouver B2 and B3 fractures would typically be managed with a revision, with the choice of implant (uncemented, cemented or proximal femoral replacement) based on fracture pattern, bone stock and surgeon preference.

Vancouver C fractures are typically managed with ORIF using a long plate with or without cables.

There are exceptions to all the above. The distinction between a B1 and B2 type injury, or even an A(L) and a B1/2 fracture is not an easy one to make, and even subspeciality consultant hip surgeons will disagree on individual cases. Occasionally, the true nature of a fracture does not become apparent until intra-operatively, in which case the plan may change even during the operation.

Guidelines

Whilst not specific to periprosthetic fractures, the BOAST for The Care of the Older or Frail Orthopaedic Trauma Patient (here) is a comprehensive overview of the management of significant injuries in this patient group, and is particularly relevant for femoral fractures.

Page details

Author: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 11/04/2020