Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

As in adults, septic arthritis in children is a serious condition which, if the diagnosis is missed or delayed, can lead to local destruction of the joint as well as systemic features of sepsis. It must be considered in any child with an acutely painful joint or who is non-weight-bearing with joint swelling/effusion and/or features of infection, especially in the absence of trauma. The primary differential is transient synovitis.

It is a surgical emergency, requiring prompt operative intervention and resuscitation.

Presentations peak in the first few years of life, with half of cases seen in children under the age of two. Although in theory any joint can be affected, the vast majority (approximately 70%) involve the hip or knee. This page is directed at these joints, but similar principles can be applied to any joint.

Infection may arise from:

- Direct trauma or surgery

- Haematogenous seeding from a distant site of infection

- Direct spread from adjacent bone affected by osteomyelitis

Differential diagnoses, particularly when affecting the hip, include:

- Trauma (including non-accidental injury)

- Transient synovitis

- Perthes disease

- Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis (SUFE)

Top tip: “Don’t be a TIT”: for any odd presentation in a child, consider Trauma (including NAI), Infection (including osteomyelitis and septic arthritis) or Tumour (sarcoma, lymphoma).

Risk factors

Whilst septic arthritis may occur in any patient, the following are considered particularly high risk:

- Premature infants

- Sickle cell disease

- Immunocompromised patients

- Invasive procedures, including umbilical vein catheterisation in neonates

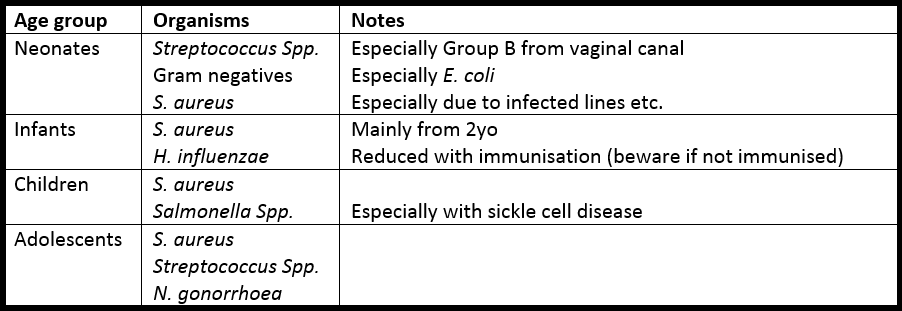

Common causative organisms

These vary by age, comorbidites and routes of infection. The following table summarises likely pathogens (information from here and here). Immunocompromised patients in particular may have unusual organisms, including (rarely) funghi.

In addition, Kingella kingae is increasingly recognised as a cause. It is more common in younger patients, may present without fever or abnormal blood tests, and commonly has negative synovial fluid MC&S. It is best detected with specific PCR tests.

Initial assessment

The typical presentation for a patient you are called to see as a ‘possible septic arthritis’ is a young child reporting pain in the hip or knee, and difficulty weightbearing.

History

As well as the usual full paediatric history (birth, milestones, immunisations etc), and a full history of the pain that the patient is experiencing (SOCRATES), there are several key points to elicit from your history:

- Recent trauma or other precipitating feature (e.g. surgical or medical intervention)

- Ability to weight-bear or otherwise (full-, non- or partial-weight bearing – FWB, NWB or PWB)

- Acute vs sudden onset of symptoms (DDH/Perthes generally have more chronic features)

- Recent illness (transient synovitis often preceded by relatively mild respiratory/coryzal/GI symptoms some days or weeks prior)

- Systemic features of illness, either infective (fevers, rigors, sweats) or tumour (loss of weight/appetite, night sweats)

Examination

As with any child, a close observation of their general appearance and interaction with parents is essential: any suspicion of non-accidental injury must be escalated appropriately.

The patient should be examined in a systematic manner, using the APLS approach if systemically unwell. Specific features are important to elicit:

- Pyrexia and/or haemodynamic changes in the presence of a painful joint are highly suspicious for septic arthritis, but be sure not to miss another source of infection elsewhere, and examine all body systems thoroughly

- Erythema, warmth, swelling/effusion or tenderness over the joint are consistent with infection; these signs are more readily apparent in the knee than the hip

- Reduced range of active and passive movement of joint: the hip is often held in FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation) which is position of comfort if large effusion present, whilst the knee is often in slight flexion

- Examine the joints above and below, including the spine; multifocal disease is possible (especially with N. gonorrhoea) and referred pain is common (especially hip -> knee)

- Weightbearing. If possible, encourage the child to try mobilising. Complete inability to WB is highly suggestive of septic arthritis or an unstable SUFE

Investigations

Bloods (liaise with paediatrics as required and cannulate at the same time):

- FBC and CRP as a minimum, plus ESR if available

- U&Es if haemodynamically compromised, systemically unwell or fewer wet nappies etc.

- Blood cultures if pyrexial

Radiographs:

- AP/lateral of any suspected infected joint

- For the hips, the lateral is typically a ‘frog leg’ view

- If doubt as to whether hip or knee is the source: obtain both series

- Often normal, but may show an effusion or may reveal an alternative diagnosis

Further imaging:

- Plain XRs are usually the only acutely available imaging outside a specialist centre. Before arranging any further imaging, at least discuss with a senior

- USS may be useful in equivocal cases to look for an effusion (and possibly aspirate to obtain a sample), but treatment of an unwell child or likely septic joint should not be delayed to obtain this: discuss with a senior!

- MRI is increasingly used to look for peri-articular osteomyelitis (either as a differential, as a source, or as a result of septic arthritis), but commonly requires a GA and is again not commonly available acutely outside of specialist centres. Again, do not delay treatment of an unwell child or likely septic joint to obtain an MRI: discuss with a senior!

Joint aspiration

- Unlike with adult septic arthritis, this is rarely a mainstay of assessment in children – it is a painful procedure that is rarely tolerated in the child (without a general anaesthetic), and may significantly traumatise them

- Teenagers may tolerate aspiration – if you are trained in joint aspiration and happy to do so, then make the decision on a case-by-case basis and following discussion with the patient and parent(s)

Initial management

If you suspect septic arthritis, or are dealing with any unwell child, do not delay: seek help from a senior and/or the paediatricians as relevant.

Obtain IV access if not already done.

Resuscitate according to APLS protocols if indicated.

Analgesia: paracetamol ± ibuprofen (unless contra-indicated).

Keep the patient nil-by-mouth (NBM).

Antibiotics:

- Conventional teaching is not to give antibiotics to a patient with a septic joint until a sample of joint fluid has been obtained but this is not a hard rule. If a child is unwell/septic then this takes priority

- If considering starting antibiotics without a joint sample, call a senior and obtain blood cultures if possible before commencing antibiotics

- Check your trust guidelines ± liaise with a microbiologist

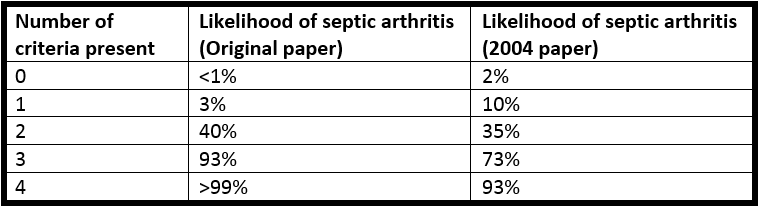

Kocher’s criteria

These are a set of four criteria, which when taken in combination are supposed to indicate the likelihood of septic arthritis in a child. They were originally developed for the hip.

One point is given for each of:

- NWB on affected side

- ESR >40 (or CRP >20 in more recent studies)

- Temperature >38.5 degrees C

- WCC >12 x 10^9/L

The following are the values given in Kocher’s original retrospective paper and in a subsequent prospective study. Even the latter numbers may be inaccurate however: septic arthritis can exist with a score of 0, and even a score of 4 does not entirely confirm the disease!

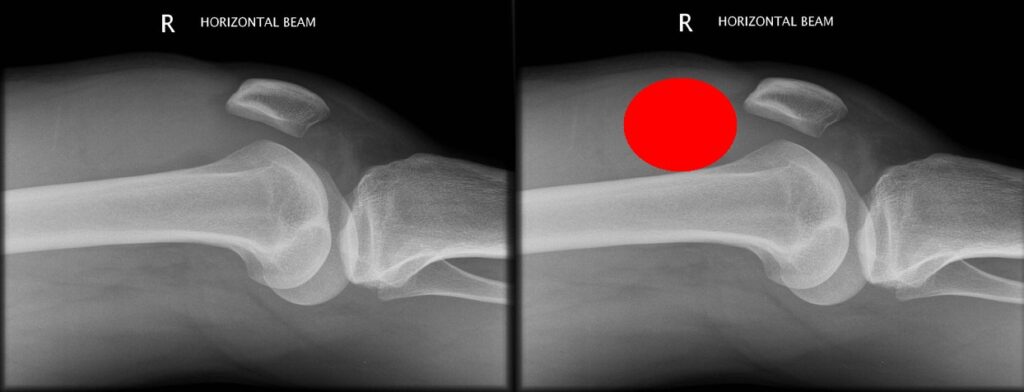

Imaging

As mentioned above, imaging is commonly normal. It may, however, demonstrate an effusion:

XRs may also show an alternative diagnosis, some of which are discussed towards the bottom of the page.

Checklist

- Documented history, examination and observations

- Senior ± paediatrician contacted if concerned

- FBC, CRP (+/-ESR), blood cultures, XR

- Sepsis management initiated if indicated – discuss with senior if considering antibiotics, before giving them

- Analgesia

- NBM

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

N.B. It is always best to err on the side of caution, call for help and admit if concerned. Rarely is this more relevant than with paediatric septic arthritis: catastrophic disability or even mortality may result from inappropriate delay or discharge

When to call a senior urgently (not an exclusive list):

- Pyrexial/unwell child with a painful joint

- 3 or 4 of Kocher’s criteria

- Not meeting above criteria, but clinical suspicion (e.g. NWB/PWB immunocompromised child)

Admission and discharge

It is impossible to define strict criteria for admission and discharge. If you are entirely happy that the child does not have a septic joint and they are systemically well, then it is reasonable to discharge overnight, but consider bringing them back for a senior review in the morning, or at least discuss in the morning for consideration of clinic review.

Patients meeting 1 or 2 of Kocher’s criteria may benefit from USS or MRI to look for an effusion or other cause of their symptoms.

Definitive management

Operative

Most septic joints undergo operative washout (opening up the joint and flushing it out with large volumes of sterile fluid). This is one of the relatively few truly urgent operations in orthopaedics (i.e. may be performed overnight).

Occasionally, joints may be aspirated to dryness, rather than undergoing formal washout.

Antibiotics

These are ideally started after a sample of joint fluid has been obtained (if considering starting without a sample, contact a senior urgently). IV antibiotics are used initially, with an oral switch once clinically and biochemically improving.

The duration of IV therapy and of overall antibiotic therapy are typically shorter than in adults.

Differential diagnoses

Trauma

Look for evidence of trauma (including nonaccidental), but beware – septic arthritis can occur as a result of trauma (e.g. superinfection of a traumatic knee effusion, or due to a graze acting as a bacterial entry point), and children fall over a lot, so trauma and infection may happen to coincide!

Tumour

A more chronic history, pain worse at night, palpable bony/soft tissue mass, systemic features (e.g. night sweats, loss of weight/appetite) or abnormal radiographs should prompt the consideration of malignancy. Rarely, joint pain may be the presenting feature of haematological malignancies – inspect the FBC carefully and discuss with a paediatrician if in doubt.

If there is any concern regarding malignancy, there should be early liaison with a senior, paediatricians and a bone tumour unit. MRI of the affected joint is indicated, but the principle is never to operate on a sarcoma unless you are the surgeon/unit that will be performing the definitive surgery.

Acute osteomyelitis

This may occur in isolation or as a cause of septic arthritis, and has similar causative organisms. The presentation is similar, but the pain may be more localised, with less loss of ROM. After 5-7 days, X-rays changes start to appear (new periosteal bone formation being the first). Particularly consider osteomyelitis if a child has a convincing presentation for infection, but a more chronic history.

Perthe’s disease

Idiopathic femoral head AVN. Itis most common in males (F:1 M:F) aged 4-8. Risk factors include family history, low socioeconomic class, Caucasian/Asian/Inuit race, breech birth and secondhand smoke. Typically has a chronic presentation, which may be with a painless limp or with isolated knee pain, as well as hip pain. Inflammatory markers/temperature should be normal. Radiographs are normal initially, then may show a smaller, sclerotic femoral head:

Slipped upper/capital femoral ephiphysis (SUFE/SCFE)

This is effectively a Salter-Harris I type fracture through the proximal femoral physis. It is most commonly seen in early adolescence (c12-13yo). Risk factors include obesity, African race, previous radiotherapy and endocrine disorders. There is a slight male preponderance. Presents with a limp and/or thigh/groin/hip/knee pain. There is often a history of low energy trauma. Inflammatory markers/temperature should be normal. The diagnosis is best made on frog-leg lateral radiographs (which again may be normal in the early stages):

Transient synovitis

This is the most common cause of acute joint pain in children. It can be very hard to differentiate from septic arthritis. The child is usually well and apyrexial, with relatively normal inflammatory markers (although these may be elevated). Whilst the ROM is reduced, they typically retain more movement than septic joints. There is often a history of a mild viral illness (upper/lower respiratory or gastro-intestinal). Treatment is with rest and analgesia/anti-inflammatories.

Page details

Author: Matt Howard

Editor: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 01/04/2020