Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

Calcaneus fractures are relatively rare but can lead to significant disability. Classically occurring due to axial loading of the foot after falling from a height, historically they were termed “lovers’ fractures” – think Romeo jumping off Juliet’s balcony after a night of passion! You may, therefore, be called to see a calcaneal fracture as part of a trauma call, as they often occur with a significant mechanism of injury, where the key to assessment and management is often to identify and treat associated injuries appropriately.

Calcaneus fractures will generally only be referred for admission if there are other injuries, if they are open, severely displaced (especially if the skin is compromised – see below – this is an orthopaedic emergency and requires overnight surgery), or if the patient is going to struggle to mobilise at home, otherwise they can be seen in fracture clinic for definitive management planning.

Initial assessment

Patients will either present as a trauma call or with pain in the heel and inability to weightbear.

Trauma calls: follow ATLS principles, and beware calcaneal fractures as a distracting injury.

Associated injuries to particularly consider:

- Contralateral calcaneus/ankle/pilon

- Tibia, especially plateau

- Femur, especially neck

- Pelvis/acetabulum

- Vertebral (10%)

History

Document the mechanism and time of injury. If this is a high-energy injury, have a low threshold for a trauma call and ATLS assessment.

Ask specifically about pain elsewhere (see list above) and head injury/loss of consciousness.

Take a full past medical history. Specifically ask about diabetes and vascular disease, both of which have significant implications for fracture healing and complications with either operative or non-operative management.

Ask about social history (important for discharge planning) and smoking status (smokers have higher rates of complications).

Examination

Perform a full secondary survey, including the regions of likely associated injury, then proceed to fully examine the affected foot:

Look: Inspect the foot: there will usually be significant bruising and swelling around the heel. Bruising spreading onto the sole of the foot should raise your suspicion (Mondor’s sign). The heel may be short and wide compared to the other side. Look for any skin compromise (blanching or tenting) or overlying wounds (follow guidance for open fractures).

Feel: expect the calcaneus to be tender, but specifically examine also the ankle and the midfoot – significant tenderness over the midfoot may indicate an associated Lisfranc type injury.

Neurovascular examination: document capillary refill, pulses and sensation over the foot. The posterior tibial pulse is often either impalpable due to swelling or too painful to examine properly, but the dorsalis pedis should still be palpable.

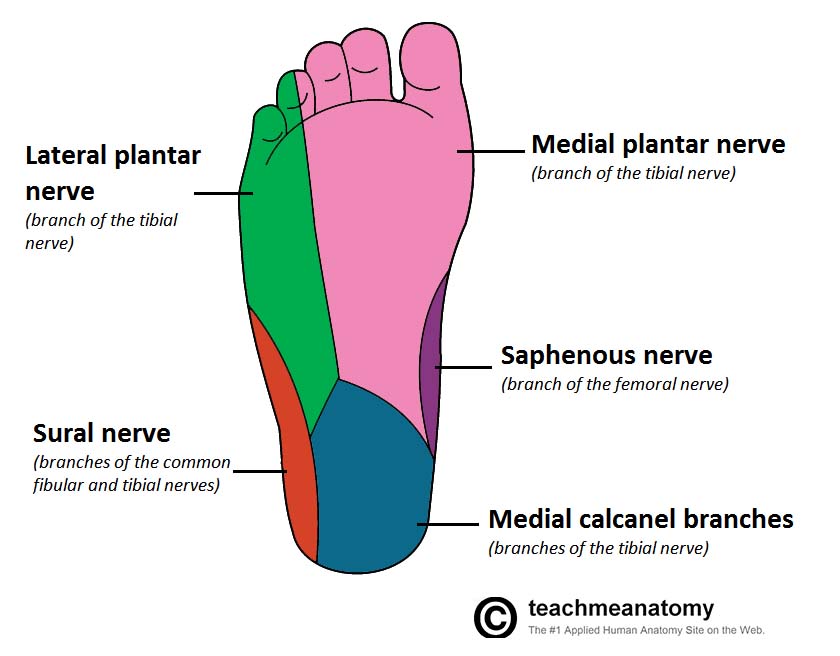

Specifically document the sensory function of the saphenous nerve (medial malleolus), superficial peroneal nerve (dorsum of the foot), deep peroneal nerve (first dorsal web space), medial and lateral plantar nerves (medial and lateral soles of the foot), medial calcaneal branches of the tibial nerve (medial heel) and the sural nerve (lateral heel).

Consider compartment syndrome if there is pain out of proportion, or significant pain on passive movements of the toes.

Imaging

Obtain plain radiographs initially. A lateral (centred on the calcaneus) and an axial view (also known as a Harris view) are the minimum required. Standard imaging of the ankle and foot may also be indicated, if you suspect associated injuries to these structures.

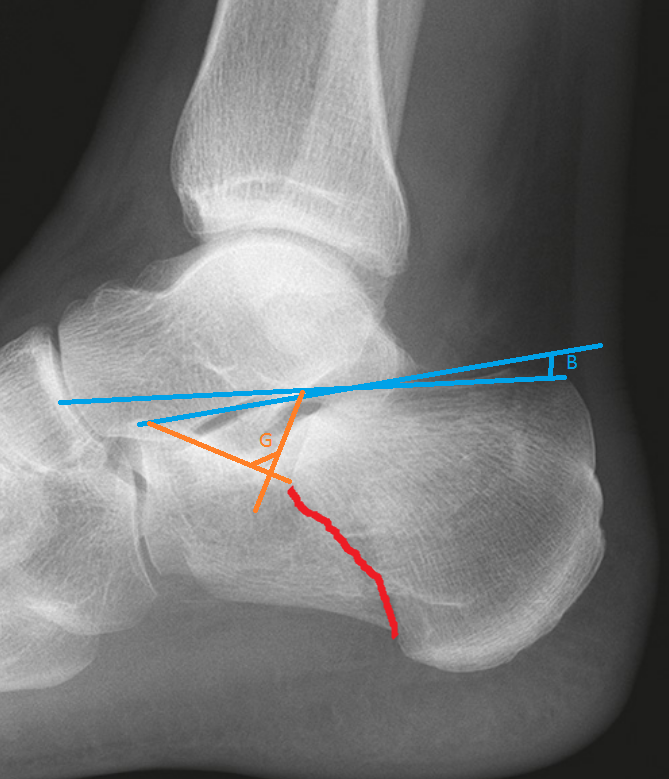

When judging fracture displacement, it is useful to consider Bohler’s and Gissane’s angles (see above). These should be 20-40 degrees and 120-140 degrees, respectively. Reduction in either angle may suggest a displaced intra-articular fracture.

If a displaced fracture is confirmed, then CT is useful to guide management (especially if an operation is required. This is not strictly required overnight, but if it is possible to obtain then makes the logistics of management easier.

Initial management

Ensure that you have appropriately investigated and managed associated injuries.

Manage an open fracture according to standard policies and guidelines (see here). This may include transfer to your local orthoplastic centre.

Fracture reduction is very rarely indicated. The exception would be a fracture that is severely tenting the skin such that it is at risk of pressure necrosis and becoming open (see below). In this case call a senior urgently and keep the patient nil-by-mouth: reduction in theatre is likely to be required.

Place the patient into temporary immobilisation (below knee backslab or an ankle boot) and keep them non-weight-bearing (NWB).

Arrange a CT if possible.

Prescribe appropriate VTE prophylaxis.

If admitting: ensure the limb is appropriately elevated (above the level of the heart). If discharging, ensure the patient has been given similar advice.

If discharging: arrange fracture clinic follow up.

Checklist

- Secondary survey to identify/rule out associated injuries documented

- Open fracture management initiated if appropriate (including transfer if indicated)

- Assessment for compartment syndrome, and appropriate initial management initiated if appropriate

- Full history, examination and XR findings documented

- Temporary immobilisation (backslab/boot) applied

- VTE prophylaxis prescribed

- CT arranged (if possible)

- Advice RE elevation

- Registrar informed and patient kept NBM if open fracture, threatened skin, vascular deficit or compartment syndrome

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

When to call a senior urgently

- Open fractures (unless being transferred to another hospital, and you are entirely happy with their management in your ED prior to transfer)

- Fractures with skin tenting

- Concern regarding compartment syndrome

- Concern regarding vascular compromise of foot

Patients to admit

- Open fractures (if you are an orthoplastic centre)

- Fractures with skin tenting

- Concern regarding vascular compromise of foot

- Concern regarding compartment syndrome

- Patients who will not cope at home (social admissions), if these are admitted under T&O in your trust

Most patients with calcaneal fractures can be managed as an outpatient, but if you are concerned, then discuss with a senior or admit – they can always be discharged in the morning.

Classification

Intra/extra-articular

75% of calcaneal fractures are intra-articular, therefore placing patients at risk of subtalar joint arthritis.

The 25% that are extra-articular may still be at risk of significant complications (e.g. skin compromise as in the example above).

Essex-Lopresti

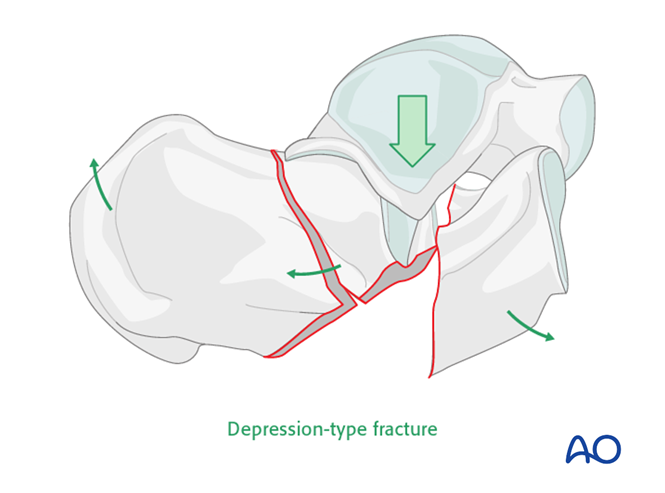

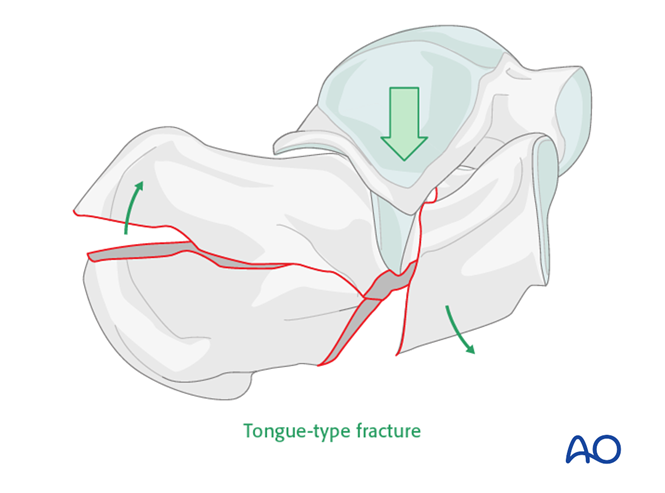

The Essex-Lopresti classification is the most-utilised descriptive classification. It is based upon the secondary fracture line, and whether it exits on the superior surface of the calcaneus (a joint-depression type) or posteriorly (a tongue-type):

Sanders’ classification

This is based on CT reconstructions of the posterior facet of the calcaneus. It ranges from I to IV with increasing number of intra-articular fracture lines.

Definitive management

Operative management is controversial – historically many intra-articular fractures have been treated operatively, however recent studies have not reliably demonstrated improved outcome with surgical intervention even in displaced fractures. What is clear, is that these fractures should be discussed with a surgeon with a subspecialty interest in foot & ankle trauma, and are not to be operated upon by other surgeons!

In general, it is thought that the main benefit of surgical fixation in severely displaced intra-articular fractures is reducing long-term rates of subtalar arthritis; this should be balanced against risks of surgery which are considerable – e.g. wound complications occur in up to 25%, with significant risks of amputation. Conservative management should be strongly considered in smokers and diabetics. Even if you think that a patient requires surgery, it is worth hedging your bets – don’t promise patients an operation. Also, be aware that surgery is usually delayed by at least ten days to allow swelling and fracture blisters to settle.

Conservative management involves:

- Non-weightbearing for 10-12 weeks

- Physiotherapy – early range of motion exercises once swelling allows

Operative management options include:

- Open reduction and internal fixation

- Closed reduction and percutaneous fixation

- Primary subtalar fusion

Postoperative complications:

NB the initial injury may lead to chronic pain, increased heel width and secondary arthritis regardless of surgical intervention.

- Wound dehiscence – especially if smoker, diabetic, high BMI, open fracture

- Compartment syndrome

- Damage to sural nerve (with lateral approach)

- Stiffness

- Chronic pain

- Increased heel width

- Malunion/non-union

- Secondary arthritis

Page details

Author: India Cox

Editor: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 09/04/2020