Jump to

Initial management and investigation

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is an orthopaedic emergency, and its management is time-critical. These patients can present with a range of symptoms, some of which are subtle, and therefore you should have a high index of suspicion when assessing patients with suspected CES. If in doubt, escalate and err on the side of caution. Missed CES can be catastrophic for patients, and accounts for a high proportion of litigation costs against doctors and the NHS.

CES is relatively rare and most commonly caused by compression of the nerves exiting the distal spinal cord (the cauda equina or ‘horse’s tail’ from around L1). This can be due to a number of pathologies, including but not limited to:

- Intervertebral disc herniation or spinal stenosis (most common)

- Epidural abscess

- Fracture

- Haematoma (especially post-operatively following spinal surgery)

- Tumour (primary or secondary)

Documentation for these patients must be thorough. If the patient is seen out of hours it can often be challenging to organise MRI scans to investigate. Some district hospitals may even have to transfer patients to regional centres in order to scan and treat CES. Make sure that you know what your local escalation policy is and what resources are available to you. Once again, if you are struggling to organise a scan that you think is necessary, you must document the cause and escalate the problem.

In some tertiary centres, CES is managed by neurosurgery, however in many hospitals it is the orthopaedic on-call who will deal with these patients.

Initial assessment

History

Take a thorough history, focusing on:

- Back pain (including any precipitating trauma etc.)

- Leg pain (unilateral, bilateral, distal extent of pain, nature of pain)

- Numbness and paraesthesia in the legs or perineum

- Leg weakness and reduced mobility

- Urinary function (ability to feel bladder filling, ability to hold urine appropriately, completeness of voiding, sensation whilst voiding, any incontinence or retention)

- Bowel function (incontinence, sensation whilst defecating)

- Infective symptoms (fevers, rigors, sweats, malaise)

- Neoplastic symptoms (loss of weight, loss of appetite, history of malignancy)

The following are commonly regarded as “red flag” history features for CES:

- Bilateral radicular pain, weakness, numbness or paraesthesia

- Saddle anaesthesia or paraesthesia

- Urinary retention (painless urinary retention is the classical textbook finding), reduced power of voiding or need to strain to PU

- Impaired sensation of urinary flow

- Urinary or faecal incontinence

Examination

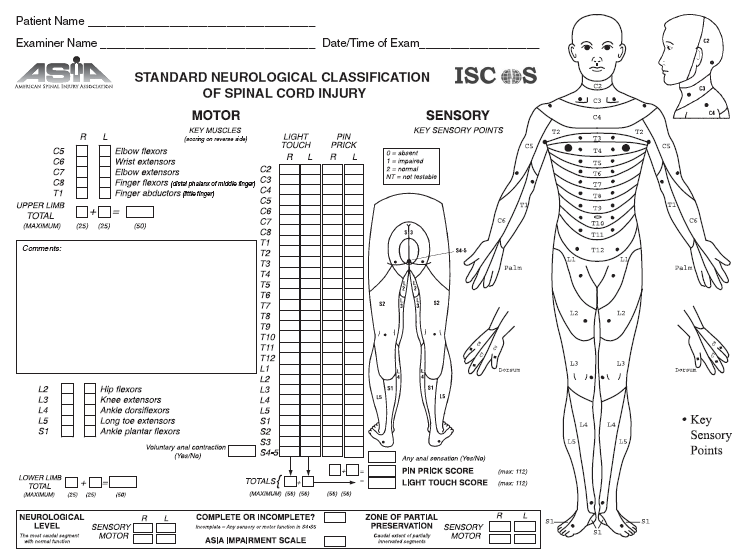

Conduct a full neurological examination of the lower limbs. If your hospital does not have its own clerking form, consider using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) form. A full neurological examination includes the following:

- Assessment of tone and presence/absence of clonus

- Myotome assessment using the MRC grading 0-5

- Dermatome assessment of light touch and pinprick sensation

- Reflexes (knee, ankle, plantar)

- Provocative tests (straight leg raise/femoral nerve stretch test)

- Gait assessment (looking for broad-based gait, foot drop, assessment of Romberg’s test) if possible

CES is a lower motor neurone condition. If you have concerns regarding an upper motor neurone lesion (increased tone, hyper-reflexia, clonus, broad-based gait, loss of proprioception) or if the patient has a history of arm pain/numbness/weakness, then also perform a full upper limb and cranial nerve assessment.

Finally, it is vital to conduct a rectal examination. Ensure that you gain consent, and have a chaperone present. Whilst the patient is in the lateral position, you can palpate their spine and paraspinal muscles for tenderness. In terms of rectal examination, check:

- Tone

- Voluntary squeeze

- Deep rectal sensation

- Perianal sensation – to both light touch and pin-prick

If a patient is catheterised, gently tug on the catheter and assess whether they can feel the sensation in their bladder (the ‘catheter tug test’).

The following are commonly regarded as “red flag” examination findings for CES:

- Bilateral sensory or motor abnormalities

- Perianal sensory loss or loss of deep rectal sensation

- Reduced anal tone or absent voluntary anal squeeze

- Absent sensation on catheter tug

Initial management and investigation

- Analgesia

- Pre/post-void bladder scans

- Catheterise if in retention (document post-void residual, catheter tug and whether they felt the insertion)

- Pre-op bloods and investigations. If the patient is on anticoagulants, these should be stopped and potentially reversed if it is safe to do so. You may need to discuss with haematology

- Do not prescribe routine VTE chemoprophylaxis (e.g. LMWH). Mechanical prophylaxis may be indicated (check your local policy). For high risk patients, discuss with haematology and a senior

- Arrange an urgent MRI lumbosacral spine if you have suspicion of CES

- Keep the patient NBM, ensuring that fasting fluids and any vital medications such as insulin sliding scales are written up

- Discuss the results of the MRI scan with a senior colleague. If there is a delay to obtaining a scan, discuss with them to determine whether than delay is acceptable

Imaging and classification

The gold standard imaging modality for CES is MRI scan of the lumbar/sacral spine. As mentioned above, compression can occur at any level, and if there is concern that the lesion may be above the level of the cauda equina, a full spine MRI should be conducted. These scans are time-critical:

- National guidelines and clinical practice are very clear: acute CES requires an urgent scan, including out of hours

- If your hospital cannot provide immediate MRI scanning, discuss with a senior

In patients for whom MRI scanning is contra-indicated (for instance in non-MRI compatible pacemakers) an alternative is CT myelography. However these may be unavailable out of hours, are in invasive scan and are more difficult to interpret. Thankfully, most modern cardiac devices are MRI-compatible.

Classification

By timing:

- Acute: typically onset of symptoms within 24-48hrs

- Subacute: onset within weeks

- Chronic: months of symptoms

- Acute-on-chronic: weeks or months of symptoms, but a definite acute deterioration

By clinical features:

- CES suspected (CESS): bilateral radiculopathy without bladder/bowel/perianal changes

- CES incomplete (CESI): some bladder/bowel changes (altered sensation, loss of awareness of need to void, poor stream, incomplete voiding or need to strain to urinate), but not in frank retention. THESE ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT PATIENTS TO IDENTIFY; once retention has developed, the outcome is significantly worse

- CES with retention (CESR): neurogenic urinary retention (painless retention) has developed. This may be described as CES complete (CESC) if there is objective loss of all cauda equine function

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Who to admit

- All cases of MRI-confirmed cauda-equina syndrome (unless they require urgent transfer to a tertiary centre)

- Anyone with an abnormal MRI, unless you have discussed with a senior and they are happy for discharge

- Anyone who needs an urgent MRI scan and who cannot have that done in the ED

When to call a senior urgently

- MRI-confirmed cauda-equina syndrome

- Urgent MRI indicated but unavailable

- Symptoms deteriorating in a patient with known or suspected CES who has already had an MRI

Checklist

- Full documented history

- Full documented examination (including rectal exam)

- Pre/post-void bladder scan

- Bloods including CRP

- MRI arranged if indicated

- Pre-operative bloods/CXR/ECG if indicated

- Patient NBM

- Anticoagulation & antiplatelets held/reversed as indicated

- Discussed with spinal surgeon/registrar as appropriate

Definitive management

The definitive treatment for confirmed CES is surgical decompression. Depending on the cause of the compression, this may involve discectomy, laminectomy, lumbar interbody fusion, posterior instrumented fusion, drainage of abscess, debulking of tumour, or a combination thereof.

In terms of timing of surgery, the principle is simple: it should be performed as soon as it can be done safely. This may require overnight operating, or transfer to a tertiary centre. As soon as imaging confirms CES, or if a patient with CES of any grade suffers a deterioration of symptoms, discuss the patient with a spinal surgeon or other senior – do not wait until the morning!

Once patients have developed urinary retention, their prognosis (even following surgery) deteriorates. Occasionally, patients with established CES (CESR or CESC) may be managed non-operatively as there may be little benefit to surgery.

Guidelines and resources

The British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS) drew up guidelines in association with the Society of British Neurological Surgeons outlining the management of CES in 2018, which can be found here.

This paper: Standards of care in cauda equina syndrome (behind paywall) provides a good overview of the clinical and medicolegal background of CES.

Medicolegal note

CES is a common and expensive cause of litigation. This is due to its poor prognosis if missed or mismanaged, its occasionally nebulous presentation, and the ability to avoid a poor outcome with appropriate and timely intervention.

It is vital to take every possible CES referral seriously, to assess the patient (clinically and, if appropriate, radiologically) in a timely manner, and to expedite their treatment to the best of your ability. I personally have a low threshold for MRI scanning – most MRI scans for possible CES are negative, reflecting the difficulties of clinical diagnosis, but the consequences of missing the diagnosis entirely are disastrous.

Accurate and timely documentation is crucial. If there is a delay to investigation or management, document the reasons why and escalate to your senior.

As with all pages on orthosho.com, this is intended as a guide only and is the personal opinion of the authors. It is not intended to replace formal training in the assessment and management of cauda equina syndrome.

Page details

Author: Paul Foster

Editor: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 29/03/2020