Jump to

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

Supracondylar fractures of the humerus (SCHs) are the most common elbow injury in children. Other less common injuries include physeal separation (Salter-Harris type injuries), media/lateral condyle fractures, dislocations, and radial head fractures. All have their own peculiarities of management, but many of the principles of assessment can be applied from SCHs to these other injuries.

Children usually present following intermediate-energy trauma (e.g. fall from monkey-bars) having fallen onto an outstretched hand. They will typically have a painful elbow, which may be deformed. Bruising in the antecubital fossa is common.

Most SCHs are relatively benign and can wait until the morning/next day for definitive treatment, but occasionally the neurovascular structures around the elbow can be injured, requiring urgent treatment to reduce the risk of permanent disability.

Initial assessment

As always, if you have any concerns regarding high energy trauma, assess with an ATLS approach.

Check distal perfusion early (skin colour, temperature and capillary refill, radial pulse), and call a senior immediately if the hand is ischaemic (no pulse and impaired perfusion).

History

Take a focussed but thorough history. AMPLE (allergies, medications, past medical history, last food/drink and events leading to injury) provides a useful template. Ask carefully about head injury and try to elicit whether there are any concerns of non-accidental injury (NAI).

Examination

- Is the injury closed or open? The only sign of an open fracture may be a pinprick wound in the antecubital fossa

- For closed fractures. is the skin in the antecubital fossa threatened? If there is skin stretched over a spike of bone, this may become necrotic within hours

- Is the hand perfused? Check capillary refill time and temperature

- Check radial pulse

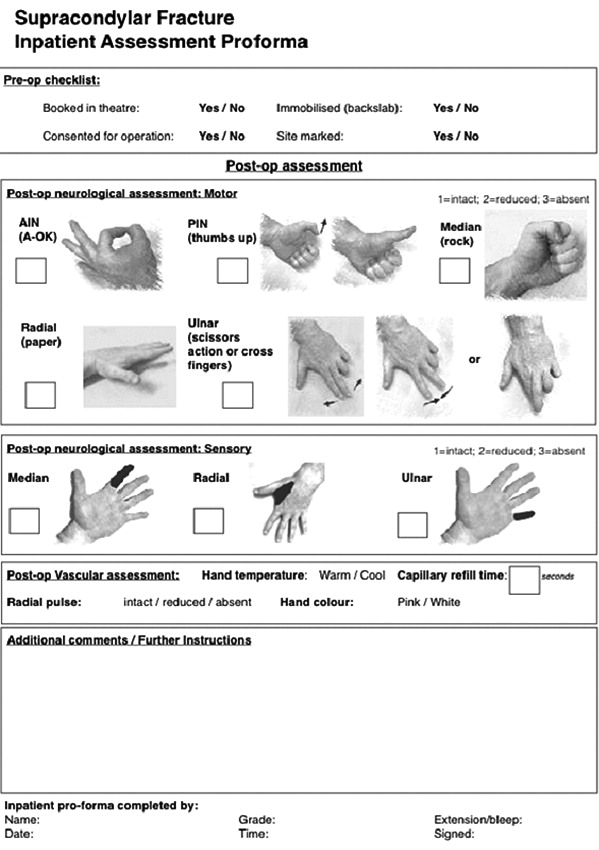

- Check neurological function of the radial, median, ulnar and anterior interosseous nerves (see below)

| Nerve | Sensory area | Motor function |

| Ulnar | Ulnar border of little finger | Abduct/adduct fingers (cross fingers) |

| Radial | Anatomical snuffbox | EPL (thumbs up) |

| Median | Volar index finger | Oppose thumb (make a fist) |

| Anterior interosseous (AIN) | None | FPL/FBP to index (OK sign) |

Below is a proforma, published in a leading journal here, which provides a handy guide to documenting neurovascular status in paediatric upper limb injuries:

Remember to check for compartment syndrome, which is rare but catastrophic. This is easiest to assess once the patient is in a backslab. At this point, the pain should much improve. Severe pain despite immobilisation, especially if it continues to increase, should raise red flags for compartment syndrome

Initial management

- Place into an above-elbow backslab in a position of comfort without flexing the elbow beyond 90 degrees (flexing the elbow can cause neurovascular compromise)

- If necessary (see below), keep nil-by-mouth and call a senior

- Consent for MUA ± open reduction ± K-wire fixation (if you feel able)

- Decide on whether to admit or discharge to return later (see ‘definitive management’)

- Advise parents on timings RE eating/drinking and when/where to return if they are going home

Imaging and classification

Below is a normal AP/lateral of a paediatric elbow. Note the various ossification centres.

With an SCH, the fracture occurs roughly at the level of the red line on the AP view. On this normal X-ray series, the anterior humeral line (green) goes through the middle of the capitellum (green circle). If there is a displaced SCH, the anterior humeral line will not go through the centre of the capitellum:

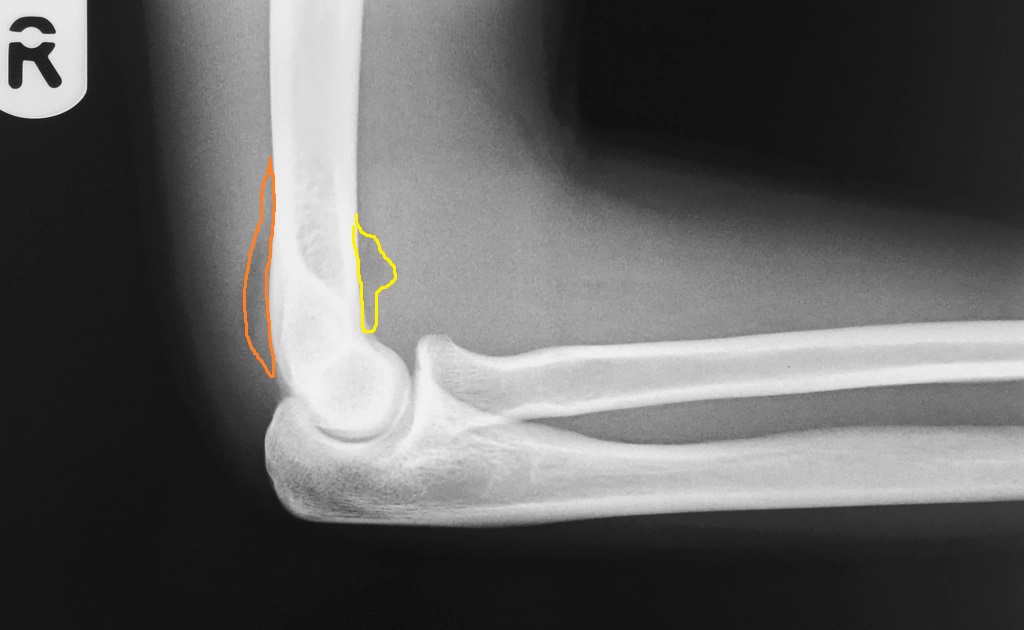

The only evidence of an undisplaced fracture may be elevated fat pads. A visible anterior fat pad may be normal, but an elevated posterior fat pad normally indicates an acute injury. If you can see an elevated posterior fat pad, or a large anterior fat pad, the safest approach is to immobilise the child with a sling (± backslab, depending on pain) and arrange a fracture clinic appointment.

Anterior and posterior fat pads

Yellow: anterior pad; orange: posterior pad

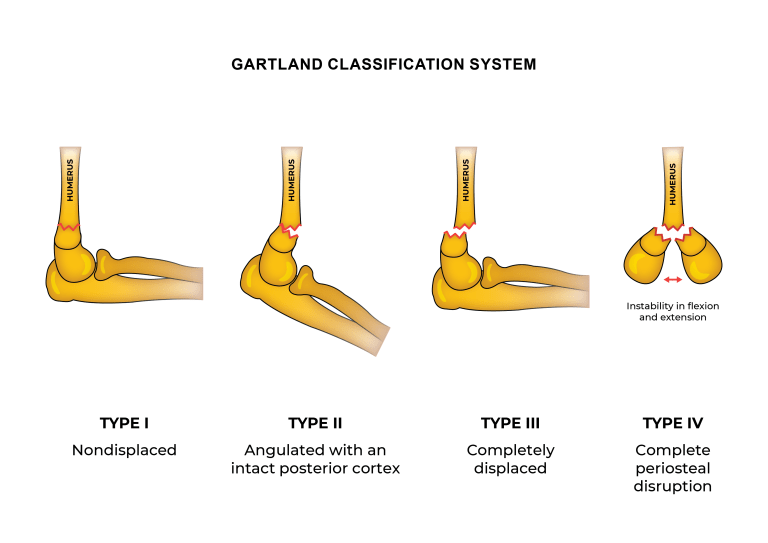

Classification

The most commonly used classification system is that of Gartland. There are various modifications, but the broad types are shown below (from Dunlop, L. Supracondylar Fractures, Don’t Forget the Bubbles, 2019):

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

When to call a senior urgently

- Open fracture or threatened skin

- Absent radial pulse or impaired perfusion of the hand

- Nerve injury

- Gartland III fracture

- Suspicion of compartment syndrome

Admission and discharge

This will vary depending on usual practice at your hospital. If you are unsure, then admit the patient, keep them nil by mouth and discuss with a senior in the morning, or let them go home, but keep them nil by mouth and arrange to call them after a discussion with a senior. My personal thought process is as follows:

Discharge for fracture clinic follow up (consider keeping starved at home, presenting in trauma meeting and calling to confirm plan):

- Gartland I with no neurovascular deficit or suspicion of NAI

- Fat pads seen but no fracture identified

Admit and keep starved for next available operating list:

- Gartland III with no neurovascular deficit

- Gartland II, but patients prefer to stay in hospital (rather than go home and return in morning)

- Any fracture with suspicion of NAI (if Gartland I, may not need to keep starved)

Allow to go home, but to return staved the next morning:

- Gartland II with no neurovascular deficit or suspicion of NAI

Checklist

- Documented history and examination

- Backslab applied

- Registrar contacted if appropriate

- Patient kept NBM if appropriate

- Admission arranged as appropriate

- Marked and consented

Definitive management

Surgical/nonsurgical management

Displaced fractures (all apart from Gartland I) are typically managed operatively, to prevent extension deformity and cubitus varus.

Surgery typically includes closed reduction (manipulation under anaesthetic/MUA) followed by fixation with smooth metal wires (K-wires), which are left poking out through the skin and a backslab applied. Occasionally (some Gartland II injuries), MUA and backslab only may be performed. The backslab may be changed for a full cast after a week (when swelling reduces) and wires are removed, usually in clinic, after 3-4 weeks. Once the wires have been removed, further casting is not normally required, but may be performed if there is ongoing pain.

Occasionally, it may not be possible to realign (reduce) the fracture closed. It has become common practice to perform an open reduction at this point, but some expert surgeons have recommended against this practice (see pages 32-33 here). Rarely, traction may be utilised for such cases.

When wires are used to fix the fracture, they may be inserted purely from the lateral side, or ‘crossed’, with one or more wires from either side. Crossed wires are mechanically stronger, and may be indicated in certain fracture patterns, but there is a risk of injuring the ulnar nerve:

Crossed wires

Three lateral wires

Timing of surgery

This is a controversial area. Immediate surgery is indicated for the following:

- Ischaemic hand

- Compartment syndrome

- Open fracture with gross contamination

Urgent surgery may be indicated for the following:

- Other open fractures

- Absent radial pulse but perfused hand (the “pink pulseless hand)

- Nerve injury

Other fractures can probably wait until the next available trauma list, but if possible, try to operate the same day, as swelling makes surgery more technically difficult. As always, if in doubt, discuss with your senior.

Guidelines

The BOA/BSCOS guidelines for paediatric supracondylar humerus fractures (BOAST 11) can be found here.

Page details

Author: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 29/03/2020