Jump to

Suspected hip fractures with normal X-rays (‘occult’ fractures)

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

Hip fractures (AKA proximal femoral fractures, neck of femur fractures, or NOFs) are among the most common reasons for admission under orthopaedics in the UK. They also require excellent medical care to prevent complications up to and including death. They are predominantly a disease of the old, and are a type of fragility fracture. They may also occur in younger people as a high energy injury; for specific aspects of managing this second group of injuries, see the relevant section below.

Good hip fracture care requires liaison between ED, T&O, ortho-geriatrics and allied specialties. The medical care of these patients is at least as important as their orthopaedic management; in this regard, the admitting SHO can vastly impact the patient’s outcome.

Your hospital will have an agreed protocol for the admission of hip fracture patients; most will have a specific clerking booklet or proforma to help you. Follow any relevant guidance in this.

Initial assessment

Primary survey

Although relatively low-energy, hip fractures occur in frail patients and may be associated with significant other injuries, which are easily missed. Starting with a primary survey a-la ATLS/ALS will help you avoid this!

History of presenting complaint

Why did the patient fall? The most common cause is mechanical (i.e. a trip or slip), but you must specifically ask the patient (and anyone else who can help, such as a family member or carer) if there was a more worrying reason for their injury. Specific things to consider include:

- Cardiac cause (MI, arrhythmia): chest pain, syncope/presyncope, unusual sweating/clamminess

- Neurological cause (seizure, ischaemic event): loss of consciousness, witness reports, tongue biting, incontinence, weakness/numbness, facial droop, aphasia

- Pathological fracture: known cancer, pre-fracture pain, fell because of fracture not the other way round, autramatic injury

- Abuse: inconsistent story from carers, bedbound patient, delay to presentation (think about similar red flags in children)

Are there any acute precipitating illnesses? Whilst most hip fracture patients have comorbidities (which you will elicit later), they may also have fallen whilst/because they have developed an acute illness. Specific things to consider include:

- Respiratory symptoms: cough, SOB, orthopnoea

- Urinary symptoms: frequency, dysuria

- Infective symptoms: fever, rigors, sweats, shivers, flu-like symptoms

- Malignant symptoms: loss of appetite/weight, blood in urine/stool/phlegm/vomit

Did they hurt anything else? Specifically ask about:

- Brain injury: hit head, LOC, amnesia, seizure

- Spine injury: pain in neck/back, paraesthesia

- Other: “does anything apart from your hip hurt?”

Past medical history

Managing comorbidities is vital. Almost all hip fractures are managed operatively. Use all the sources available to help you (patient, carers, family, care home records, GP records, hospital records/discharge summaries). Specific things to consider include:

- Cardiac: ischaemia, arrhythmia, failure

- Respiratory: COPD/asthma, bronchiectasis

- Diabetes

- Cancer (important to ask about previous/current treatment and presence/absence of known metastases)

- Neurological: epilepsy, Parkinson’s

Drug history

Ask about allergies/intolerances. Obtain as full a DHx as possible, using all the same sources as for your past medical history. Specific medications to consider:

- Anticoagulants (clarify timing of last dose)

- Anti-platelet agents

- Corticosteroids

- Anti-Parkinsonian medications

- Cardiac medications (anti-hypertensives, rate controlling agents, diuretics)

Social history

This is vital in determining the patient’s orthopaedic management and predicting likely outcomes. Specifically, record:

- Residence (house, flat, bungalow, warden-controlled housing, residential home, nursing home)

- Care needs

- Mobility and walking aids both indoors and outdoors

- Smoking and alcohol use

Examination

Check the observations chart: patients may be hot (infection) or cold (exposure), bradycardic (heart block, medications) or tachycardic (arrhythmia, sepsis, dehydration, bleeding, pain), hypotensive (arrhythmia, sepsis, dehydration, bleeding) or hypertensive (missed medications, pain).

‘Orthopaedic examination’:

- Affected leg: likely to be shortened and externally rotated. Check neurological (distal sensation and ability to wiggle toes) and vascular (foot perfusion and pulses,) status. Check skin for ulcers. Gently roll leg to confirm which side is painful, then put a permanent marker arrow on the thigh

- If there is doubt as to whether there is a fracture or not, then check for tenderness over the GT and in the groin, pain on rolling the leg/rotating the hip, ability to SLR and to weight bear

- Spine: check for midline spinal tenderness

- Other limbs/rest of affected limb: examine systematically for bruising, tenderness, pain on movement and obvious deformity

‘Medical examination’:

- Breath sounds, dyspnoea, orthopnoea

- Heart sounds

- Abdominal tenderness

- Peripheral oedema

Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS)

- Age

- DOB

- Place

- Year

- Time

- Years of WWII

- King/Queen or Prime Minister

- Identify two people

- Recall address (42 West Street)

- Count down 20-1

Investigations

All patients:

- AP pelvis XR (+/- lateral depending on institution; personally I think all extracapsular fractures and un/minimally displaced intracapsular fractures require a lateral)

- CXR

- ECG

- Bloods: FBC, U&E, group & save (x2 if no previous samples on system)

Selected patients

- ABG if hypoxic or unwell (for lactate)

- CRP if infection suspected

- Troponin if cardiac ischaemia suspected

- Bone profile & LFTs if cancer/pathological fracture suspected

- Clotting studies if anticoagulated (especially warfarin)

- Cultures as indicated if infection is suspected (blood, sputum, urine, wound swab)

- CT head & neck if head injury suspected

Initial management

N.B. Treat any concurrent/precipitating illness. The below describes an ‘uncomplicated’ management plan

N.B.2 Follow your trust protocol. The below is provided as an example

- Analgesia: local anaesthetic nerve block in ED ( anticoagulation is not a contra-indication); regular and PRN analgesia. E.g. fascia iliaca block, regular paracetamol, regular oramorph 2.5mg QDS, PRN oramorph 2.5-5mg Q2hrs

- Laxatives (regular) and anti-emetics

- Write up regular medications. Anti-parkinsonian medication must be given on time (liaise with medics if this might be problematic). Hold anticoagulants and any medications that might provoke AKI (unless the benefit outweighs the risk e.g. furosemide if overloaded)

- Anticoagulation: hold all; reverse warfarin and recheck INR as per trust protocol

- Steroids: follow trust protocol for patients on long term steroids

- Build up drinks: most trusts have a protocol for high energy pre- and post-op supplements

- Anti-diabetic medications: follow trust protocol. Insulin-dependent diabetics may require a sliding scale

- Feeding: if the patient might get to theatre today, keep them NBM; if not, allow food & drink, then starve from 0200 (water until 0600)

- IV fluids: prescribe slow IV fluids (e.g. Hartmann’s 10hrly)

- VTE prophylaxis: as per trust protocol

- Blood tests: write in notes. Transfuse if Hb <100

- Pressure area care: air mattress, C-view dressings on heels, sacrum & elbows

- Discuss and document resuscitation/treatment escalation status

- Mark and consent for operation if you feel competent to do so

Traction

The vast majority of cases do not require traction, will not benefit from traction, and may even be harmed by it (especially young patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture). It may, however, be of use for significantly displaced/angulated extracapsular fractures, especially subtrochanteric fractures.

You won’t go far wrong if you put all subtrochanteric fractures into skin traction, whilst leaving all other fractures out of traction. Again, if you’re not sure, speak to a senior.

Imaging & classification

Classification

There are multiple classifications, but the simplest and most useful is to describe the fracture using standardised terminology. Consider, in order:

- Is the fracture intracapsular or extracapsular?

- Within those two classes, where is the fracture anatomically?

- Is it displaced or undisplaced?

- For extracapsular fractures, what is the obliquity of the main fracture line and how many parts are there?

Intracapsular vs extracapsular

This is a vital distinction. Displaced fractures inside the hip capsule potentially compromise the blood supply to the femoral head, so they are usually treated with arthroplasty. Fractures outside the joint capsule do not damage the blood supply to the femoral head, so are usually fixed.

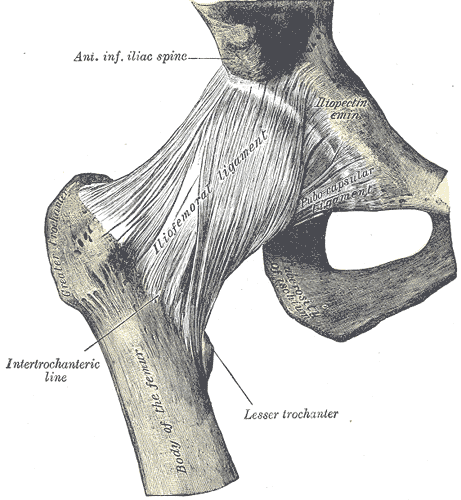

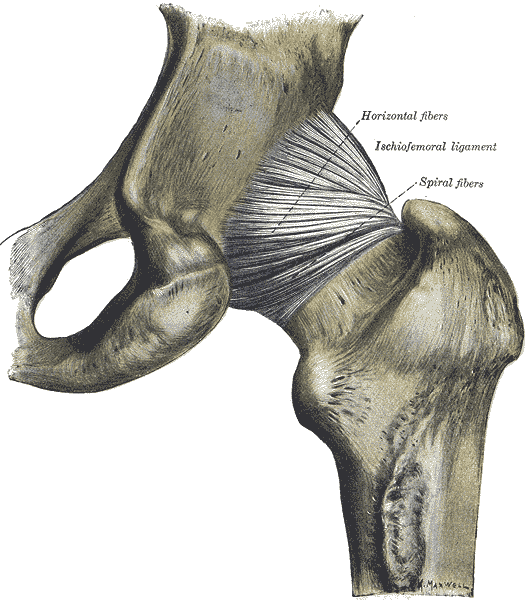

Anteriorly, the joint capsule attaches along the intertrochanteric line (from the greater to the lesser trochanter. Posteriorly, however, the attachment is more proximal – between 1/3 and 1/2 way up the neck. See the diagrams below:

Anterior view (from Gray’s anatomy via Wikipedia)

Posterior view (from Gray’s anatomy via Wikipedia)

Intracapsular fractures

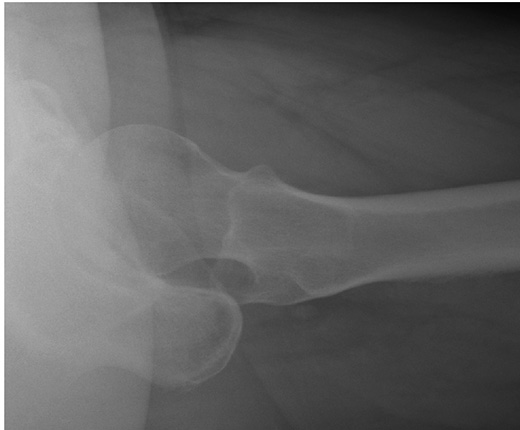

These may be obvious, such as the example shown below:

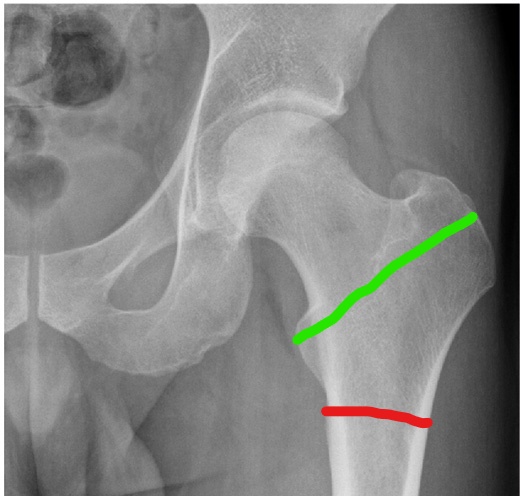

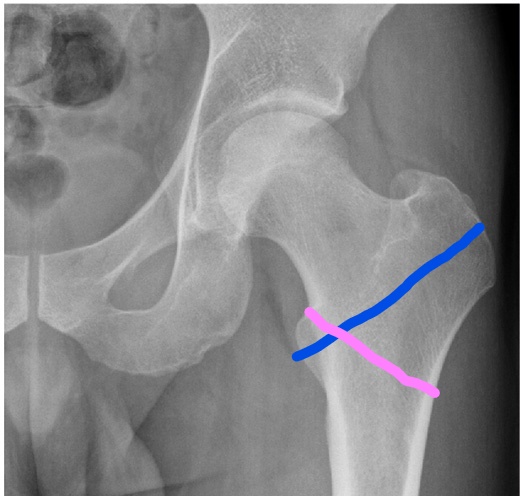

If the AP radiograph looks normal, look closely at the lateral. These are not always easy to interpret, but do so systematically. Top of the XR is always anterior, with the bottom of the XR posterior. Identify the femoral shaft, femoral neck and femoral head. The head should be perfectly central on the neck (“the ice cream on the ice cream cone”). If the head is ‘off the back’, this may be the only radiographic evidence of a fracture:

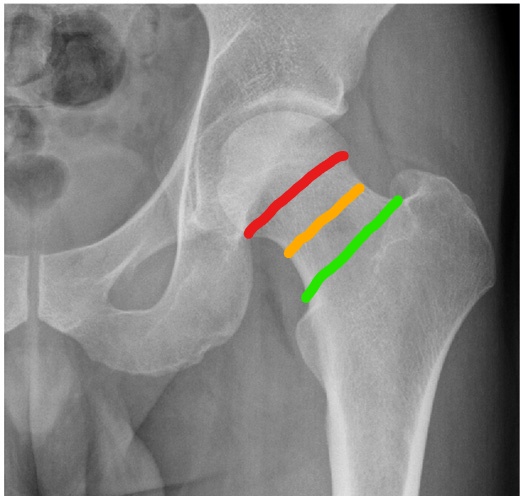

Intracapsular fractures may be described as being “subcapital” (latin: sub = below, capital = head), “midcervical” (cervical = neck) or basicervical. Basicervical fractures are usually classified as being intracapsular, but because the capsule (and hence the blood supply to the head) actually attaches partway up the neck posteriorly, they may be treated with fixation instead of arthroplasty.

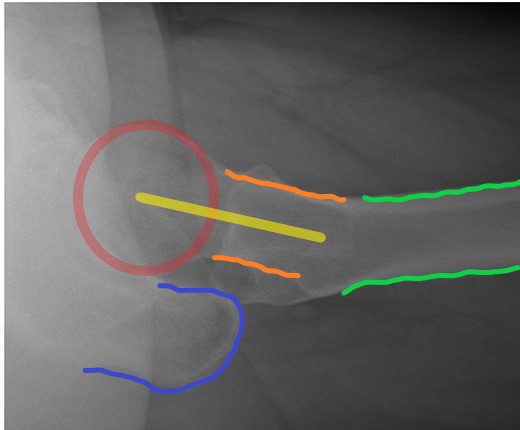

Intracapsular fractures: red = subcapital; amber = midcervical; green = basicervical

Extracapsular fractures

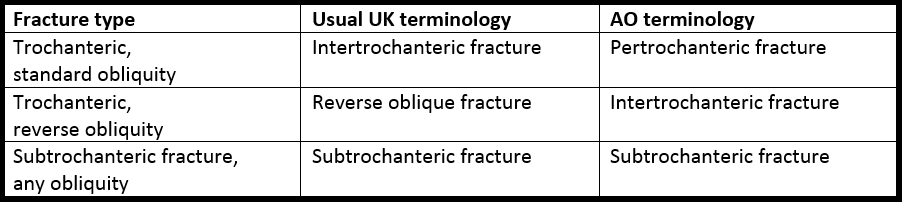

The terminology regarding extracapsular fractures can be confusing, with the words used in ‘day-to-day’ practice differing from the ‘official’ terminology of AO (the international ‘ruling body’ of fracture fixation). The variables that describe an extracapsular fracture are whether it is “trochanteric” (between/at the level of the trochanters) or “subtrochanteric” (up to 5cm distal to the lesser trochanter) and, for trochanteric fractures, whether the obliquity of the fracture is standard or reverse (see below).

The level and obliquity of the fracture then determine what overall name is given to the injury. As mentioned above, this terminology differs rather unhelpfully:

Finally, comment on the number of fracture fragments, where the maximum number is four (shaft, head & neck, lesser trochanter, greater trochanter). You can then describe the fracture, for example, as a “three part reverse oblique extracapsular fracture”.

Hip fractures in the young

The vast majority of hip fractures are fragility fractures from low energy injuries. Hip fractures in younger patients are different for two reasons:

- Higher energy injury. It takes a lot of force to break a non-osteoporotic femur. The chance of other, potentially life-threatening, injuries is therefore high.

- Different priorities for definitive management. Elderly displaced intracapsular fractures are managed with arthroplasty (see below). In order to avoid an unnecessary hip replacement in a young person, we typically fix even displaced intracapsular fractures in this age range. Time is of the essence to reduce the risk of subsequent femoral head avascular necrosis.

In practical terms, this means three things for the T&O SHO on call:

- Young intracapsular fractures should be managed as per ATLS, with a low threshold to put out a trauma call and to obtain a trauma CT scan. Look for associated injuries (e.g. spinal & pelvic fractures).

- Call the registrar if you identify a displaced intracapsular fracture in a young patient – some centres/surgeons will reduce and fix this injury overnight

N.B. ‘Young’ is a relative term, which in this context is impossible to define. It takes into account both the patient’s chronological and biological age. Personally, I would expect a call about any hip fracture aged <40, and anyone 40-65 without major medical comorbidities.

Suspected hip fractures with normal X-rays (‘occult’ fractures)

Not all hip fractures are visible on initial plain XRs. If there is a clinical suspicion of a fracture, and the AP looks normal, insist on a proper lateral XR (‘horizontal beam lateral’). If this still looks normal, then NICE guidlines are to:

“Offer magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if hip fracture is suspected despite negative X-rays of the hip of an adequate standard. If MRI is not available within 24 hours or is contra-indicated, consider CT.”

In practice, CT is more readily available, more comfortable for the patient, and more appropriate for a confused patient than MRI, so many hospitals will CT initially if XRs are negative. If XR and CT are negative, and there is ongoing clinical concern, then MRI should be performed.

If CT/MRI cannot be performed in the ED, then your hospital should have a protocol for which specialty admits elderly patients whilst they await their scan (T&O or medicine).

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Who to admit: all hip fractures

When to call a senior urgently:

- Most hip fractures do not need urgent senior review – this can wait until the morning unless you have specific concerns (e.g. associated arterial injury)

- If you require help with medical optimisation, call the appropriate medical specialist

- Call your orthopaedic senior about young hip fractures, especially displaced intracapsulars

Checklist

- NOF proforma completed

- Full clerking history (Hx, PMHx, DHx, SHx) recorded

- Secondary survey recorded

- ECG, CXR and bloods recorded

- Hb >100 or transfusion arranged

- Cannula sited and IV fluids prescribed

- Regular medications written up

- Contra-indicated medicines being held

- Anticoagulation being reversed

- Analgesia (including nerve block), anti-emetics and laxatives prescribed

- Nutritional support prescribed

- Pressure area care being managed

- Resuscitation decision documented

- Next of kin aware (if appropriate)

Definitive management

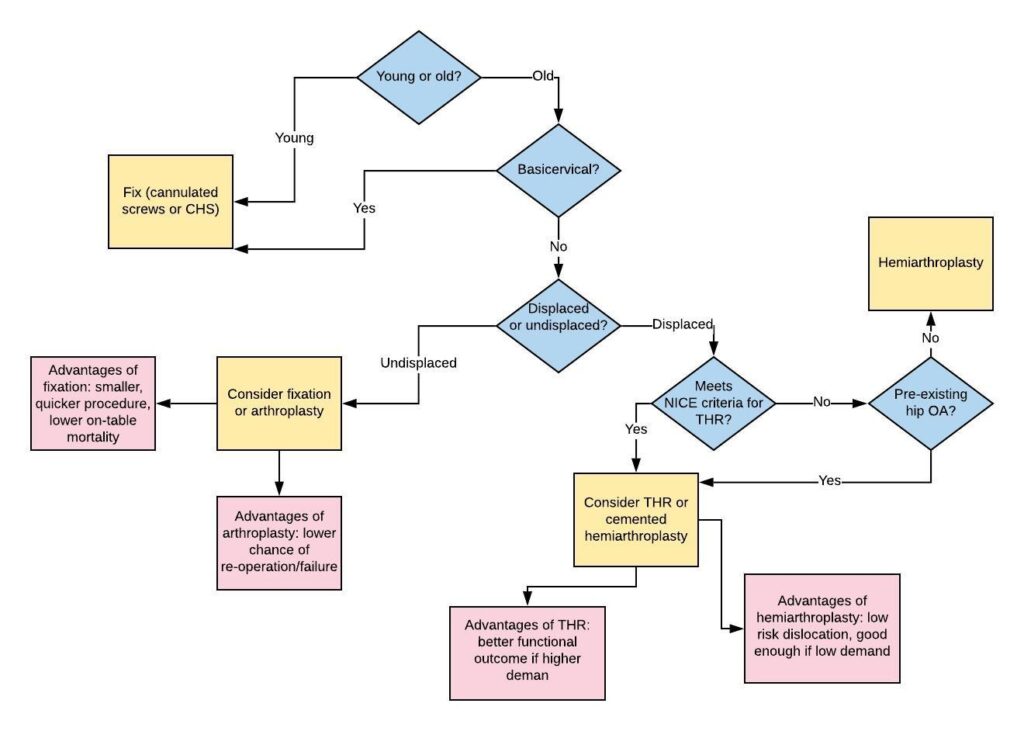

Intracapsular fractures are predominantly treated with a cemented hemiarthroplasty, but may be fixed (using cannulated screws or a DHS) if the patient is young or has an undisplaced fracture. If the patient is best served by a joint replacement, but meets the criteria below, they should be considered for a total hip replacement (THR) instead of a hemiarthroplasty:

- Independently mobile outside (1 stick or less outside)

- Cognitively intact (most surgeons would say AMTS 8 or more)

- Medically fit for the procedure (ASA I-II, possibly III)

See below for a flow chart illustrating the decision making process regarding treatment of intracapsular fractures:

Extracapsular fractures are almost universally fixed. Fixation may be with an extramedullary device (e.g. a Dynamic Hip Screw, DHS) or an intramedullary device (a cephalomedullary nail). NICE recommends a DHS for all fractures apart from subtrochanteric and reverse oblique fractures, but some practice varies.

Guidelines

The original BOAST guideline for hip fractures can be found here. It has since been superceded by a more generic BOAST for frailty trauma, which you can find here.

NICE guidelines may be found here.

Page details

Author: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 29/03/2020