Jump to

Reducing fractures in the emergency department

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Overview

This page is specifically regarding adult injuries. In time we hope to create a specific article on corresponding paediatric injuries.

As with all orthopaedic trauma, distal radius fractures may be high- or low-energy. Most can be safely managed non-operatively and without hospital admission, but there are important exceptions.

The most common mechanism for a distal radius fracture is a fall on out-stretched hand (FOOSH). Patients present with a combination of pain in the wrist/distal radius, deformity and loss of range of movement.

Initial assessment

As always, these may be high-energy injuries, and it is important not to miss a life-threatening other injury – consider ATLS primary survey.

History

Document the mechanism and any other painful areas. Remember that a painful wrist is a distracting injury, and patients may neglect to mention other important injuries, especially the hip (older patients) or head and spine.

Ask about neurovascular symptoms in the hand:

- Neuropathic pain/tingling

- Numbness

- Severe distal pain

Take a full past medical, social (including hand dominance and smoking status) and drug history.

Examination

Assess the skin over the fracture site. Is there an open injury, or is the skin threatened? If the skin over the fracture is severely contused, stretched over the fracture, ischaemic (white) or necrotic (dark blue/black) then there is a risk of a closed fracture becoming open. Is there visible deformity?

If there is visible deformity and pain, it is reasonable not to assess the fracture site itself any further. If not, palpate for bony tenderness of the distal radius and ulna. If these are relatively pain free, check for a clinical scaphoid fracture (tenderness in the anatomical snuffbox, over the scaphoid tubercle and pain on axial loading of the thumb).

Again, if there is visible deformity, consider not assessing movement. Otherwise, gently ask the patient to flex, extend, pronate and supinate, assessing for pain and range of movement.

Document distal vascular status (capillary refil, radial and ulnar pulses).

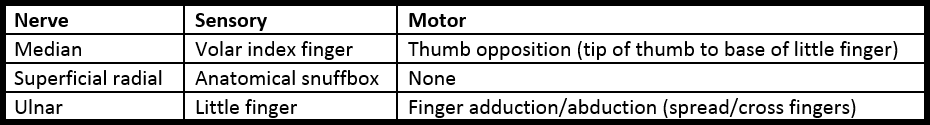

Document distal neurological function:

Imaging

Obtain PA and lateral radiographs (if these have not been done already). Consider adding a ‘scaphoid series’, which includes additional views of the scaphoid, if you are clinically suspicious of this injury (not particularly tender over distal radius/ulna, but more so over the scaphoid itself), or if a patient has significant pain, but initial wrist XRs show no fracture.

Reducing fractures in the emergency department

N.B. The aim of this page is not to teach you to reduce fractures. You must ensure you are appropriately trained before performing any interventions. It is not possible to succinctly write a “guide to wrist fracture reduction” – every fracture is different and has its own ‘character’.

N.B.2. The decision of whether or not a fracture needs reducing is entirely unrelated to whether or not it is going to need operative management. Once the fracture is reduced, the patient’s pain will improve as will their swelling and bruising. The tension is taken off neurovascular structures, and (if there is an intra-articular element), abnormal pressure on cartilage is relieved, reducing the risk of long-term arthritis. If there is a delay to surgery, it is better for the fragments to be well-aligned, so that soft tissues do not contract. Most importantly, even fractures that appear terrible on admission, may be treated without an operation if they are well reduced in the emergency department. Do not accept “they’re going to need an operation anyway” as a reason not to reduce! This also applies to open fractures, where reducing the fracture (after removing any gross contamination) will reduce bacterial colonisation of the bones and fracture site.

Deciding whether a fracture needs reducing

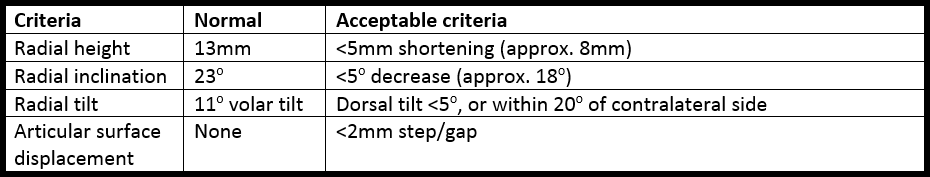

ED staff usually have a good understanding of which fractures need reducing, and which do not. As always, if you are unclear, discuss with a senior. Commonly used indices for what is acceptable/unacceptable include:

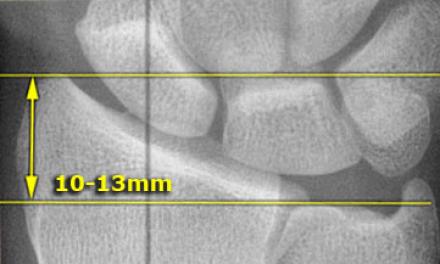

- Radial height (measured on PA): the distance between two lines, which are drawn perpendicular to the long axis of the radius. One is level with the distal ulnar articular surface, and the other with the tip of the radial styloid

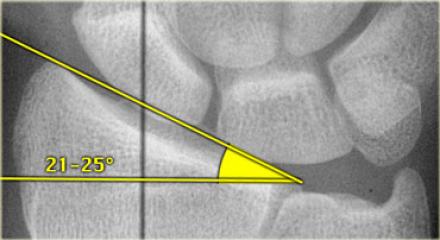

- Radial inclination (measured on PA): the angle between two lines, one drawn perpendicular to the long axis of the radius, and the other connecting the tip of the radial styloid and the ulnar corner of the distal radius

- Radial tilt (measured on lateral): the angle between two lines, one drawn perpendicular to the long axis of the radius and the other connecting the volar and dorsal rims of the joint surface

- Articular surface displacement: visible splits or steps in the articular surface

The table below lists normal and acceptable ranges for these measurements (from orthobullets), but it is impossible to be proscriptive. If you are unsure, it is best to err on the safe side and call for help. If someone has a fracture that falls outside these criteria (apart from the articular surface displacement), but without significant pain or external deformity, check whether they have had a previous fracture to that wrist, and consider imaging the contralateral side: there is significant variation and they may have had an odd-looking wrist before the injury!

The majority of distal radius fractures are dorsally displaced/angulated, and the criteria regarding tilt refer to these injuries. Have a low threshold for arranging manipulation of volarly displaced/angulated injuries.

Regarding extra-articular displacement (translational – angulation is covered in the above indices), it is unusual to have significant displacement without affecting the indices in the table. If, however, there is significant translation in either the dorsal/volar or radial/ulnar directions, then this should be reduced. What is significant? It’s hard to say, but I would consider reducing anything displaced by more than one cortex-thickness.

Neurovascular deficits in the presence of a fracture also mandate reduction.

Logistics of fracture reduction

As mentioned above, if you’re not confident in fracture reduction and haven’t been appropriately trained, you shouldn’t be doing it, but the following is a useful checklist:

Prepare

- Documented pre-reduction neurovascular status

- Verbal consent from patient

- Analgesia/sedation and someone to administer it if needed

- Plaster trolley and someone to help apply the plaster

- Someone to provide counter-traction

- If there is an open fracture: saline-soaked gauze and occlusive dressing

Perform

- Manipulate as required

- Wound dressing for open fracture

- Apply a plaster splint (radial splint/backslab or volar slab depending on fracture; some fractures may be placed immediately into a full cast, but this is less common, and the cast should be split to allow for swelling)

Check

- Re-check and document neurovascular status

- Arrange, review, and document result of check X-rays

Initial management

Manage open fractures as per any open fracture (for guidance see here and here).

If the fracture requires reduction, arrange this.

If no reduction is required, place the patient into either a back/volar slab or a removable splint (e.g. Futuro splint) depending on local policy and stability of fracture. If you are unsure which is more suitable and there is no local policy, a backslab may be safer.

Provide a sling and advise patients to elevate their hand as much as possible and to keep moving their fingers – this will not make the fracture displace and reduces the future risk of complications including complex regional pain syndrome. If possible, provide an advice leaflet.

Unless there is an associated injury, neurovascular deficit, open fracture or social reason for admission, most patients can be discharged from ED.

Checklist (for simple closed neurovascularly intact injury)

- Documented history and examination, including neurovascular status

- Fracture reduced if appropriate, with documented post-reduction neurovascular exam and check XRs

- Appropriate immobilisation applied

- Patient advice leaflet or appropriate advice given

- Fracture clinic arranged

Admission, discharge and calling a senior

Who to admit

- Open fractures

- Fractures with a neurovascular deficit

When to call the registrar urgently

- Open fracture that requires urgent debridement (see here)

- Persistent neurovascular deficit after reduction

- New neurovascular deficit after reduction

- Fracture requiring reduction, but you/ED are not able/willing to do so

- Unacceptable position despite reduction

If you are uncertain about whether a fracture will need an operation, but the position is acceptable and there are no obvious reasons for admission or to call a senior, then a safe approach is to let the patient go home, but to take their contact details and advise them to be nil by mouth the next morning. You can then discuss with a senior or at the trauma meeting and contact the patient to advise on the necessary next steps.

Definitive management

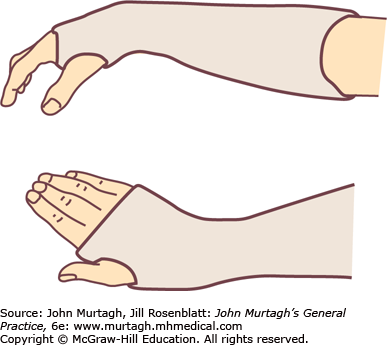

The primary options for distal radius fractures are operative or non-operative (for the majority). Non-operative management includes treatment in a cast or removable splint (e.g. Futuro splint). The period of immobilisation is variable, but may be up to six weeks in rare cases (2-4 weeks is more common). Historically a “Colles’ cast” was commonly used, but a neutral below elbow cast is more frequently employed now. The difference is the position: a Colles’ cast positions the wrist in flexion and ulnar deviation (to try and correct the deformity of extension and radial deviation), whilst a neutral cast is in the normal anatomical position).

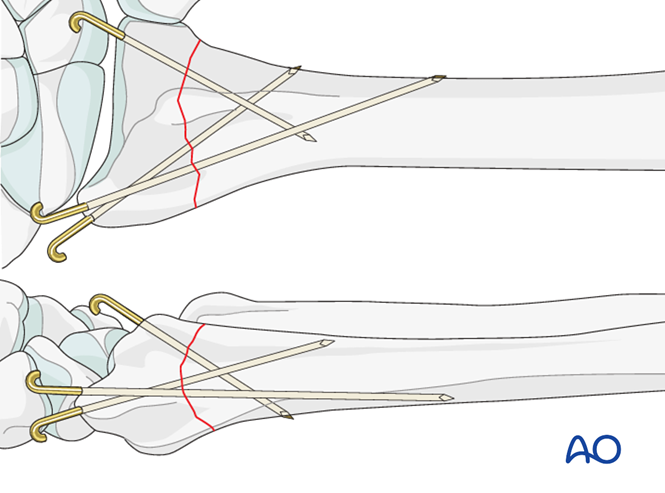

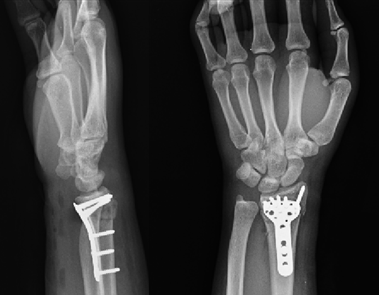

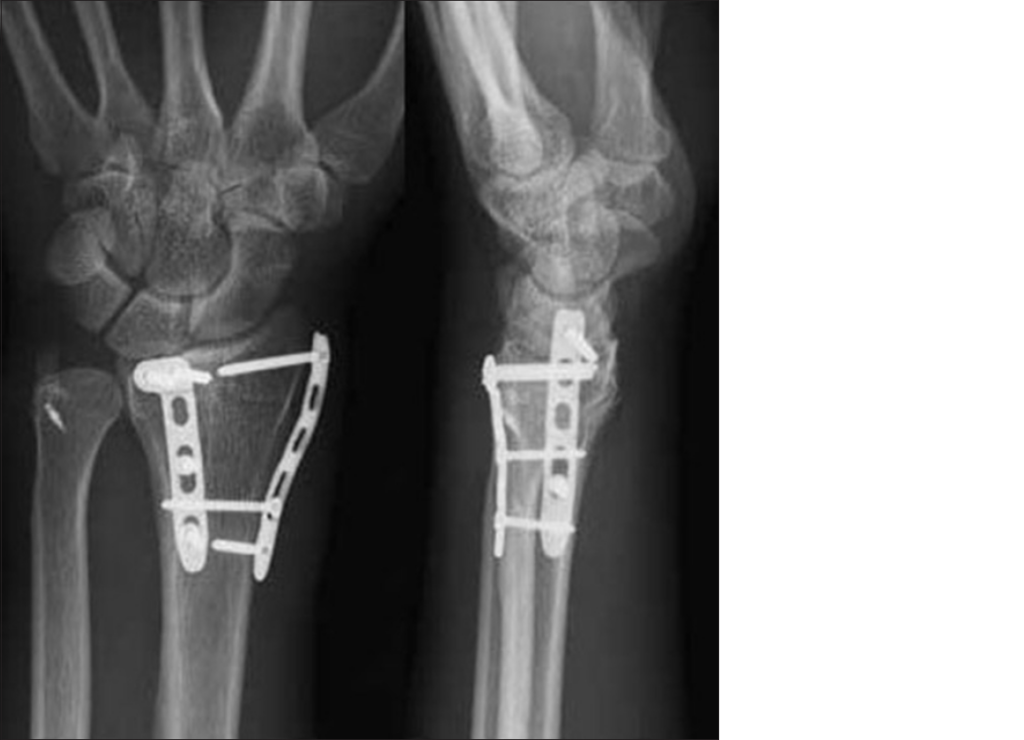

Operative treatment may be with smooth metal pins (K-wires) combined with a plaster cast (often called “MUA & K-wires) or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), with a plate and screws. ORIF is generally performed from the volar aspect, but certain fractures may be treated with a dorsal plate, and some are even fixed from the volar and the dorsal aspect.

External fixators are an option, but are less commonly used than in the lower limb. For temporary stabilisation, a backslab is usually sufficient. For patients with a very comminuted fracture, particularly with osteoporotic bone, a salvage option may be an “in-fix”, where a dorsal plate is applied to span from the distal radius to a metacarpal (across the wrist joint) and is usually removed after around six weeks.

Guidelines and evidence

The British Orthopaedic Association Standard for Trauma (BOAST) can be found here.

The British Society for Surgery of the Hand (BSSH) has produced a thorough but very readable guide to the management of distal radius fractures, which can be found here.

A commonly-quoted trial, DRAFFT, can be found here. It is not without its methodological problems, but suggests there is no benefit of ORIF over MUA & k-wires for most distal radius fractures in the elderly. It should not be interpreted, however, as suggesting that all osteoporotic distal radius fractures can be managed in this way. DRAFFT2 (MUA & k-wires vs. MUA without K-wires) is currently in progress.

Associated/similar injuries

Just because someone doesn’t have a distal radius fracture, doesn’t mean that they don’t have a significant injury to their wrist. Someone can also have a distal radius fracture and another significant injury. Hopefully we’ll be able to provide specific pages for some of these conditions, but for now, consider the following:

Septic arthritis (especially if minor trauma and other features of infection).

Scaphoid fracture. Consider this diagnosis even in the absence of a fracture on XRs, as a proportion are not visible on initial imaging. If you suspect a scaphoid fracture, then immobilise the patient (backslab or splint as for a distal radius fracture) and arrange fracture clinic review. A missed scaphoid fracture can cause severe early osteoarthritis.

Carpal dislocation. These patients present in a very similar manner to distal radius fractures and may be present with fractures of the distal radius and/or scaphoid. Median nerve impairment is common, and if the dislocation is not reduced urgently this may become permanent. Suspect a carpal dislocation if there is pain and/or deformity and odd-looking XRs. If immediate reduction is not possible, call a senior urgently.

Scapholunate ligament injury. This presents in a similar manner to distal radius fractures, scaphoid fractures or carpal dislocation. The patient may give a history of a ‘clunk’ at the time of injury or afterwards. Imaging may be normal, or show a widened scapholunate interval. It is usually safe to discharge the patient from ED with a splint, but discuss with a hand surgeon and arrange rapid follow up.

Page details

Author: Hamish Macdonald

Last updated: 29/03/2020